Quick Summary

Table of Contents

The Wildlife Protection Act 1972 is India’s foundational law for conserving wildlife, habitats, and biodiversity. Enacted amid a drastic post-independence wildlife decline highlighted by the extinction of the cheetah and a sharp fall in national parks it provided the first comprehensive legal framework for protecting animals, plants, and ecosystems. It authorized the creation of protected areas like national parks, sanctuaries, conservation/community reserves, and tiger reserves. This law also introduced vital institutions such as the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL), Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB), and Central Zoo Authority, making India a signatory to CITES.

With regular amendments over decades including in 1986, 1991, 2002, 2006, and as recently as 2022 the act has dynamically evolved to meet modern conservation challenges, like human-wildlife conflict and habitat degradation

The government can create national parks and wildlife refuges to protect ecosystems and species under this law. These regions’ biodiversity is protected by stricter laws. Poaching, hunting, and the illegal trade in wildlife and their products are all severely punished by this Act with prison time and hefty fines.

Throughout the ages, India’s rich biodiversity has been a source of admiration. The evolution of wildlife conservation in India is a fascinating journey reflecting the country’s rich biodiversity and the challenges it has faced.

Wildlife has always shaped India’s cultural and natural heritage in its vast and diverse landscape. However, wildlife resource exploitation increased in the 20th century. Rapid urbanization, deforestation, and human-wildlife conflicts caused this. National wildlife protection and regulation require a strong legal framework. This urgent need prompted India’s wildlife conservation law. This law protected wildlife and balanced human development and natural habitats.

The Wildlife Protection Act 1972 (WLPA) safeguards India’s wildlife through three key objectives:

These objectives work together to create a comprehensive framework for wildlife conservation in India.

The Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, draws its authority from the Indian Constitution, which establishes a clear duty for both the state and citizens to protect the environment.

A major change introduced by the Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Act, 2022, was the rationalization of the species schedules. The old six-schedule system was consolidated into four to reduce complexity and align with India’s obligations under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

| Schedule | Focus & Level of Protection | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Schedule I | Species accorded the highest level of protection. Hunting, trade, etc., invite the most severe penalties. | Tiger, Elephant, Snow Leopard, Gangetic Dolphin, Great Indian Bustard, Marine Turtles. |

| Schedule II | Species that are also protected but offenses attract lesser penalties than Schedule I. | Birds like the Indian Hornbill, Grey Mongoose, and several snake species. |

| Schedule III | Comprises protected plant species whose cultivation and trade are regulated. | Specific orchids, pitcher plants, and other threatened flora. |

| Schedule IV | Consists of species listed in the CITES Appendices. This ensures international trade in these species is regulated through a permit system. | Although some may also be in Schedules I or II, this schedule explicitly includes species like the Saker Falcon and certain shark species to enforce CITES. |

The Act establishes specialized institutions to guide and implement its provisions.

| Governing Body | Establishment | Key Role & Function |

|---|---|---|

| National Board for Wildlife (NBWL) | Section 5A | The apex advisory body, chaired by the Prime Minister. It reviews and approves all projects related to ecologically sensitive protected areas and formulates wildlife policy. |

| State Board for Wildlife (SBWL) | Section 6 | The state-level counterpart to the NBWL, chaired by the Chief Minister. It advises the state government on wildlife conservation and management. |

| National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) | 2006 Amendment | A statutory body chaired by the Union Environment Minister. It oversees the “Project Tiger” initiative, manages tiger reserves, and provides technical and financial support for tiger conservation. |

| Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB) | 2008 (Via a 2006 Amendment) | A specialized agency to combat organized wildlife crime. It collects intelligence, assists international coordination, and trains enforcement officials. |

| Central Zoo Authority (CZA) | 1992 Amendment | Regulates and monitors all zoos in India to ensure they maintain scientific and professional standards for animal housing and care. |

While the WPA has been amended several times (1986, 1991, 2002, 2006), the most recent and significant change is the Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Act, 2022.

Key Implications of the 2022 Amendment:

The Act sets aside some areas to protect the habitats important for many species’ survival.

Sanctuaries are protected areas where animals, birds, and plants are allowed to live without any human intervention. This is a safe space for injured, abandoned, and abused wildlife creatures to roam freely, feed, breed, and live in harmony with their surroundings. Sanctuaries allow limited human activity.

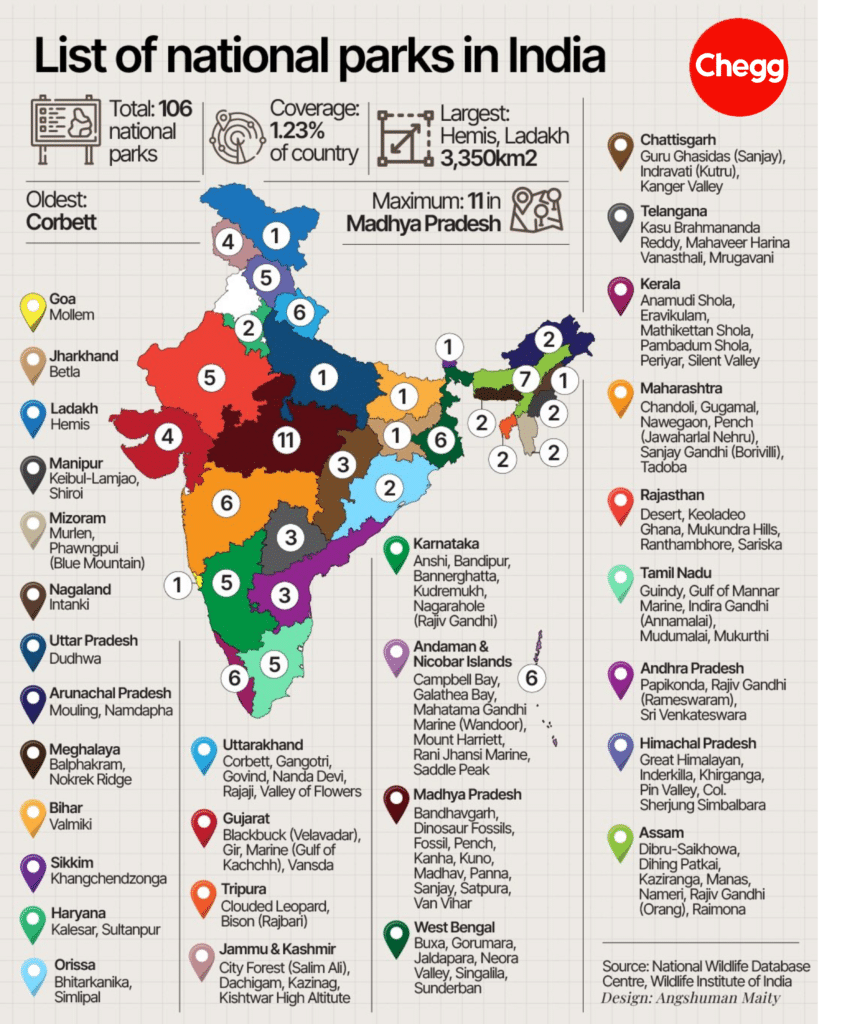

National Parks are vast areas of land preserved by the government for the enjoyment of the public and the protection of natural ecosystems. These areas often feature diverse landscapes, including forests, mountains, and water bodies, and are home to a wide variety of plant and animal species. National parks have more rules and regulations than sanctuaries and they do not allow any human activity.

Conservation Reserves are designated areas used for the conservation and protection of wildlife and their habitats. These reserves aim to maintain biodiversity and support endangered species by implementing measures to prevent habitat destruction and promote sustainable land use practices.

Community Reserves are conservation areas managed by local communities in collaboration with government agencies and conservation organizations. These reserves empower communities to take an active role in wildlife protection and habitat management, fostering a sense of stewardship and ownership among residents.

Tiger Reserves are specialized conservation areas established to protect the habitat of endangered tiger populations. These reserves focus on preserving critical tiger habitats, implementing anti-poaching measures, and promoting coexistence between tigers and local communities to ensure the survival of these magnificent creatures.

By taking these precautions, the Wildlife Protection Act has become a turning point in India’s conservation history, ensuring the country’s abundant biodiversity for future generations.

Despite its achievements, the Wildlife Protection Act (WPA) of 1972 faces significant implementation hurdles and has been the subject of ongoing debate, particularly regarding its social impact and adaptability.

1. Persistent Enforcement Gaps

The Act’s effectiveness is hampered by ground-level enforcement challenges. Poaching and illegal wildlife trade remain severe threats, fueled by insufficient frontline staff, a lack of advanced resources for patrolling India’s vast wilderness, and instances of corruption. This gap between the law’s strict provisions and on-the-ground reality undermines its power.

2. Escalating Human-Wildlife Conflict

As habitats fragment due to urbanization and development, animals are increasingly pushed into human-dominated landscapes. Incidents of crop raiding by elephants, leopard attacks in villages, and livestock depredation by tigers have become common. The WPA lacks a comprehensive framework to address these tensions, leading to rising resentment among affected communities and retaliatory killings of animals.

3. The Conservation vs. Development Dilemma

India’s push for economic growth and infrastructure often directly conflicts with conservation goals. Critical wildlife habitats are frequently threatened by projects like dams, roads, and mining operations. While the NBWL assesses such projects, the process is often contentious, highlighting the immense challenge of balancing ecological preservation with national development objectives.

4. Socio-Economic Impact on Local Communities

A major criticism of the Act is its impact on forest-dwelling and tribal communities, such as the Sapera and Kalandar tribes. The establishment of protected areas has, in some cases, led to their displacement and the criminalization of their traditional livelihoods and cultural practices, which were historically sustainable. This has sparked debates about integrating community rights and justice into the conservation model.

5. Limitations in Protecting Marine Ecosystems

The WPA’s framework is primarily designed for terrestrial ecosystems. This has created a significant enforcement gap in marine conservation. Species like sea cucumbers face severe threats from illegal trade, but enforcement remains a major hurdle in vast coastal areas, revealing a critical blind spot in the legislation.

6. Debates Surrounding the 2022 Amendment

The recent 2022 Amendment, while strengthening the legal framework with stricter penalties, has sparked debate. Critics argue that without robust, complementary community-centric conservation programs, these heightened punishments could further alienate and penalize local populations, exacerbating existing tensions rather than fostering cooperation.

Read More:-

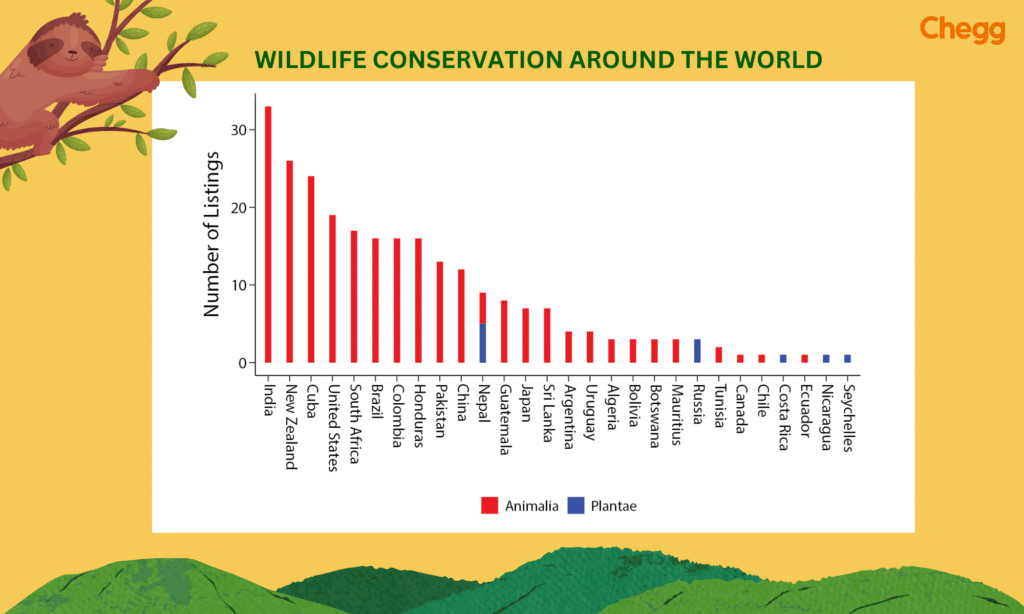

Many countries have passed strict legislation to protect their wildlife, as this issue has gained international attention. The contrast between the Wildlife Protection Act of India and similar laws in other countries shows valuable insights.

India is active in international conservation forums like CITES, Ramsar, and IUCN. The Wildlife Protection Act is the cornerstone of these efforts because it establishes a domestic framework that aligns with international commitments. We can learn lessons from successfully conserving tiger populations in India and elsewhere to better protect biodiversity.

The Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, has evolved dynamically, growing from a foundational text into a complex legal instrument. It has undeniably saved iconic species from the brink and cemented a conservation ethos in national policy. However, its future effectiveness hinges on addressing its legacy of social impact and adapting to modern ecological crises. The true test will be moving beyond a purely protectionist model to one that fosters coexistence, addresses climate change, and integrates environmental justice for both wildlife and the people who live alongside it.

The purpose of this law is to safeguard endangered species and the places they call home. It frequently contains clauses about the creation of protected areas, hunting laws, and steps taken to stop the illegal trade in wildlife products.

Each country has a different year of enactment. For instance, the Indian version was enacted in 1972, while the enactment dates for other countries vary.

The act may include mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and even plants on its list of protected species. Priorities tend to shift toward protecting endangered and vulnerable species.

The Wildlife Protection Act 1972 includes six schedules.

To prohibit hunting and commercial trade of specified wildlife.

To safeguard flora and fauna through stringent legal protection.

To set up a network of protected areas (e.g., national parks, sanctuaries).

To establish monitoring bodies like the NBWL, Central Zoo Authority, and WCCB.

To support international conservation agreements such as CITES

Authored by, Muskan Gupta

Content Curator

Muskan believes learning should feel like an adventure, not a chore. With years of experience in content creation and strategy, she specializes in educational topics, online earning opportunities, and general knowledge. She enjoys sharing her insights through blogs and articles that inform and inspire her readers. When she’s not writing, you’ll likely find her hopping between bookstores and bakeries, always in search of her next favorite read or treat.

Editor's Recommendations

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.