Quick Summary

Table of Contents

Tributaries of Yamuna form the backbone of one of North India’s most vital river systems. The Yamuna River, often revered as the lifeline of northern India, is the second-largest tributary of the Ganges and one of the most sacred rivers in Hindu tradition. Its waters nourish agriculture, sustain life, and have deep cultural and religious significance. The Yamuna plays a vital role in the region’s economy and ecology by flowing through key states like Uttarakhand, Haryana, Delhi, and Uttar Pradesh.

But what makes the Yamuna river system remarkable is its network of tributaries, some mighty, others seasonal, each contributing uniquely to the river’s flow and health. From glacier-fed origins to rain-dependent seasonal streams, these Yamuna tributaries form a vast hydrological web across the northern plains.

Understanding the Yamuna basin’s structure and each tributary’s role is crucial for sustainable water management, agriculture, and environmental preservation in one of India’s most densely populated regions. In this guide, we’ll explore the tributaries of Yamuna, where the Yamuna originates from, key ecological zones, and more.

Understanding where the Yamuna originates from and how it flows through northern India is essential to grasping the full scope of the Yamuna river system and its impact on the region’s geography, culture, and economy.

The Yamuna originates from the pristine Yamunotri Glacier, nestled in the Bandarpoonch massif of the Lower Himalayas in Uttarkashi district, Uttarakhand. Situated at a towering altitude of around 6,387 meters (20,955 feet) above sea level, this glacier marks not only the physical source of the river but also serves as a revered spiritual site in Hinduism. The Yamunotri Temple, dedicated to Goddess Yamuna, draws thousands of pilgrims annually, especially during the Char Dham Yatra season.

The Yamuna’s initial flow is swift and turbulent, cutting through steep Himalayan terrains, gorges, and valleys. Its glacier-fed origin gives the Yamuna a perennial flow, although downstream stretches face seasonal fluctuations due to overuse and pollution.

The Yamuna travels approximately 1,376 kilometers from its glacial birthplace before meeting the Ganga at the sacred Triveni Sangam in Prayagraj (Allahabad), Uttar Pradesh. Along the way, the river passes through four central Indian states, each relying on it for agriculture, industry, and urban needs:

Read More: Tributaries of Ganga

The Yamuna’s banks have fostered some of India’s most iconic cities:

In Hindu mythology, Yamuna is the daughter of Surya (the Sun God) and sister of Yama (the God of Death), so bathing in the river is believed to absolve sins and ensure salvation. Geologically, the river’s formation is linked to the tectonic uplift of the Himalayas, and it plays a vital role in shaping the Indo-Gangetic plains by depositing nutrient-rich alluvium, sustaining millions through agriculture.

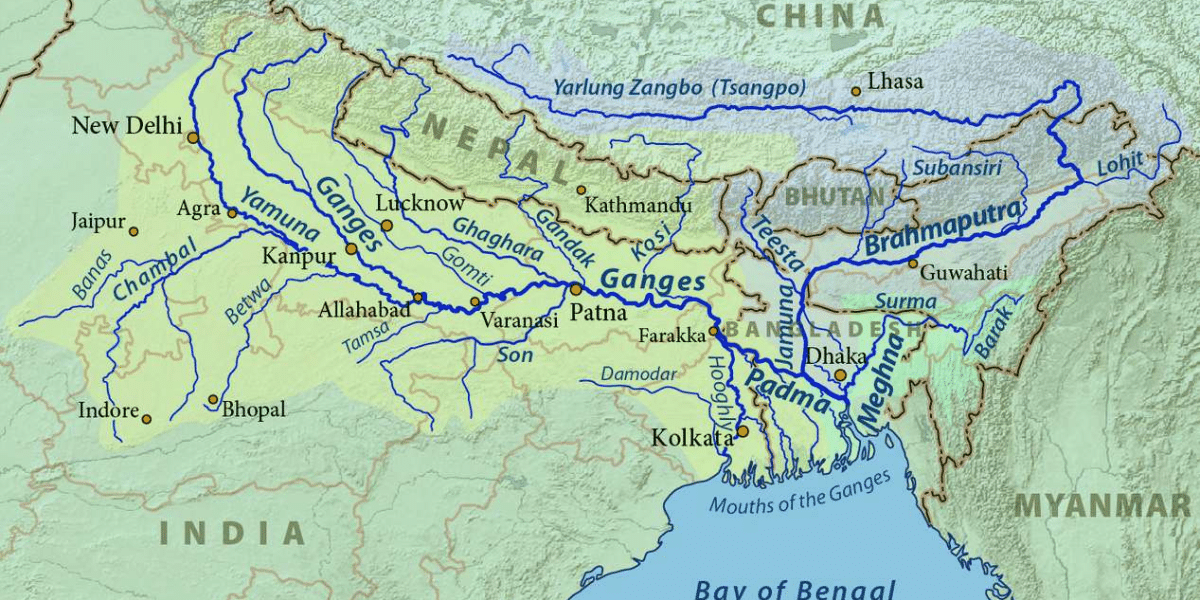

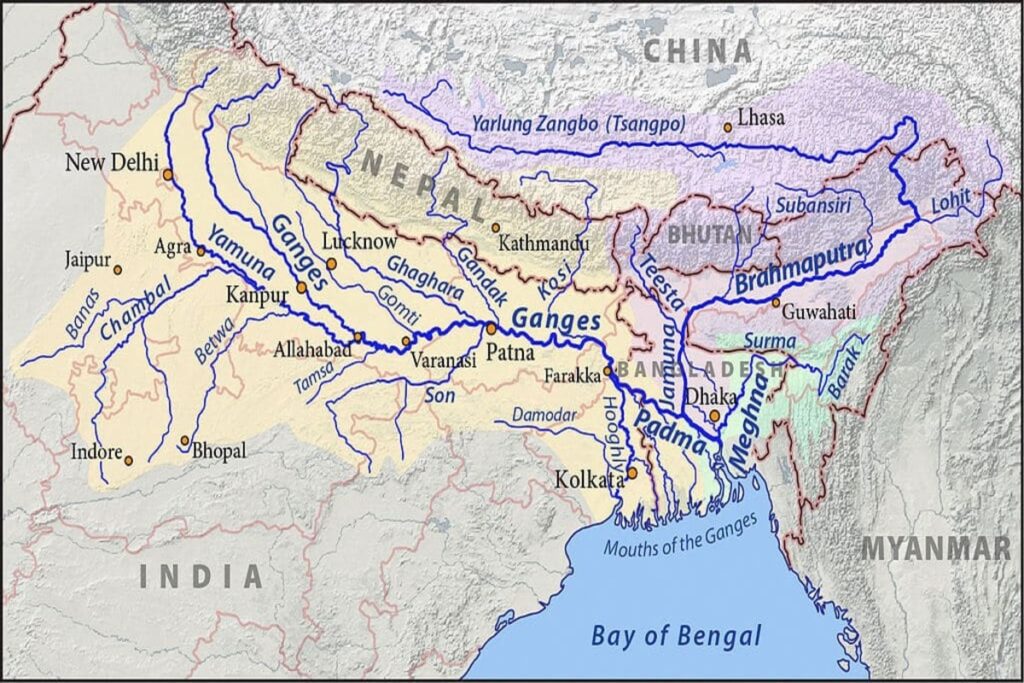

Understanding the Yamuna river map is key to grasping this vital river system’s geographical expanse, environmental diversity, and hydrological structure. The Yamuna river system covers vast terrain from its glacial origin in the Himalayas to its confluence with the Ganga at Prayagraj. Along its path, it supports multiple ecosystems, cities, and communities.

A look at the Yamuna River map highlights its journey through northern India and the complex network of tributaries, both perennial and seasonal, that contribute to its flow. These tributaries enhance the river’s volume, recharge groundwater, and ensure water availability for agriculture and daily use.

The Yamuna river basin spans 366,223 square kilometers, making it one of India’s largest and most important river basins. It flows through seven states:

This vast coverage makes the basin integral to water distribution in the country’s mountainous and plain regions.

The Yamuna River system interlinks with the Ganga River system, forming a critical part of northern India’s hydrology. This interconnected network is crucial in sustaining biodiversity, regulating floods, and maintaining agricultural productivity.

The tributaries of the Yamuna play a crucial role in shaping northern India’s hydrological, agricultural, and ecological character. These rivers vary greatly in origin, size, and contribution. Some arise from Himalayan glaciers and flow perennially, while others are seasonal and rain-fed. Together, they form an extensive and dynamic Yamuna river system, supporting agriculture, water supply, biodiversity, and cultural traditions.

The Tons River is the largest tributary of Yamuna in terms of water discharge. Interestingly, at their meeting point in Kalsi, the Tons often carries more water than the Yamuna itself. Originating from the Bandarpunch Glacier, the same glacial system that feeds the Yamuna, the Tons flows through the rugged terrains of Garhwal and parts of Himachal Pradesh, carving deep gorges and valleys.

Being a perennial river, the Yamuna is a key component of the upper Yamuna basin. It holds immense potential for hydroelectric power and is considered ecologically rich, hosting diverse flora and fauna.

The Chambal River is one of the longest and most ecologically significant Yamuna tributaries. Flowing through the heart of central India, it is known for its deep gorges, clean water, and rare aquatic life. The Chambal has remained relatively unpolluted due to minimal urban development along its course.

Its basin supports the Chambal Wildlife Sanctuary, home to endangered species such as the gharial, mugger crocodile, and the Ganges river dolphin. Chambal is also fed by several sub-tributaries, including:

Together, these rivers form an essential sub-system within the Yamuna basin.

The Hindon River is a monsoon-fed tributary that flows through western Uttar Pradesh. Although it once supported agriculture and groundwater recharge, decades of industrial effluents and untreated sewage have turned it into one of the most polluted rivers in the country.

Efforts under various rejuvenation programs aim to restore the Hindon’s flow and ecological health. Measures include installing sewage treatment plants (STPs), restricting industrial waste discharge, and community-led cleaning drives.

The Ken River is a major right-bank tributary of the Yamuna. Flowing through the Panna Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh, the Ken is known for its crystal-clear waters, scenic waterfalls, and diverse wildlife.

It has been the center of national attention due to the Ken-Betwa River Linking Project, India’s first river interlinking plan. This plan aims to divert water to drought-prone Bundelkhand. While this promises irrigation benefits, it raises serious concerns about ecological damage, especially to the Panna ecosystem.

The Betwa River is another key tributary that sustains the semi-arid Bundelkhand region, known for water scarcity and frequent droughts. Flowing through both Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, the Betwa is dammed at several points, including the Rajnagar and Rajghat Dams, which supply water for irrigation and drinking purposes.

Despite being seasonal in parts, the Betwa is crucial to the region’s rural economy, supporting large-scale farming and animal husbandry.

The Sindh River is a right-bank tributary that flows through fertile agricultural regions. It supports irrigation in multiple Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh districts and contributes significantly to local food production, especially wheat and paddy.

While relatively less discussed in mainstream narratives, Sindh is vital in regulating floodwaters during the monsoon and aiding in groundwater recharge across its basin.

The Giri River is a small but significant left-bank tributary of the Yamuna. Originating from snow-clad peaks, it remains perennial and supports micro-irrigation schemes in Himachal Pradesh. The Giri helps maintain water levels in the upper Yamuna zone and is considered ecologically clean.

Its role becomes crucial when other seasonal streams dry up during the dry months. The river also carries cultural importance in the regions it passes through.

| Tributary | Source Location | Length (km) | Confluence Location | Type |

| Tons | Bandarpunch Glacier, UK | ~690 | Kalsi, Uttarakhand | Perennial |

| Chambal | Janapav Hills, MP | ~1,024 | Near Etawah, UP | Perennial |

| Hindon | Shivalik Hills, UP | ~400 | Near Momnathal, UP | Rain-fed |

| Ken | Kaimur Hills, MP | ~427 | Near Chilla, UP | Perennial |

| Betwa | Vindhya Range, MP | ~590 | Near Hamirpur, UP | Seasonal |

| Sindh | Sehore, MP | ~415 | Near Etawah, UP | Seasonal |

| Giri | Jubbal, Himachal Pradesh | ~150 | Near Yamuna Nagar, HR | Perennial |

These major tributaries of Yamuna are not just water bodies but ecological corridors, cultural symbols, and economic lifelines for millions. Protecting them is essential for ensuring a resilient and sustainable Yamuna River system.

In addition to its major rivers, the Yamuna river system includes several minor and seasonal tributaries that play crucial roles, especially during the monsoon season. Though smaller in size and flow, these rivers contribute significantly to groundwater recharge, local irrigation, and flood management.

While these tributaries may not contribute large volumes year-round, they are ecologically significant. They help regulate monsoonal water flow, improve soil moisture, and support rural livelihoods in their regions.

The Yamuna tributaries are more than just water sources; they are lifelines that nourish agriculture, sustain ecosystems, and preserve rich cultural traditions across northern India.

The tributaries irrigate extensive agricultural belts in Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, and Madhya Pradesh. Canals and distributaries drawn from rivers like the Betwa, Ken, Sindh, and Hindon enable the cultivation of staple crops such as wheat, rice, sugarcane, and pulses. In regions like Bundelkhand, these rivers are critical to overcoming water scarcity and ensuring food security.

Tributaries like the Yamuna support fragile ecosystems. The Chambal River Sanctuary is home to endangered species such as the Gharial, Indian Skimmer, and river dolphin. The forest corridors along these rivers serve as biodiversity hotspots, offering critical habitats for flora and fauna.

Many tributaries carry deep cultural and religious meaning.

The Yamuna river system and tributaries face severe ecological stress due to unregulated development, pollution, and unsustainable usage.

To address these challenges, basin-wide integrated water resource management, sustainable policies, and active community involvement are urgently needed to restore and preserve the health of the Yamuna tributaries.

| Year | Event |

| Vedic Era | Yamuna is mentioned in the Rigveda |

| 1900s | The first canals from the Yamuna were constructed |

| 1993 | Launch of Yamuna Action Plan |

| 2022 | Ken-Betwa River Linking cleared |

| 2024 | Yamuna is mentioned in Rigveda |

Efforts to restore the Yamuna River system and its tributaries have recently intensified through national and regional initiatives.

Together, these efforts are crucial for ensuring the long-term sustainability of the Yamuna system.

The Yamuna tributaries are integral to India’s natural, cultural, and agricultural landscape. Tributaries uniquely sustain the larger Yamuna River system from the snow-fed Tons River, the ecologically rich Chambal, and the spiritually significant Hindon.

These rivers support millions of livelihoods, nourish fertile farmlands, preserve endangered wildlife, and hold immense religious and historical value. Yet, growing pollution, overuse, and mismanagement threaten their survival. Protecting the Yamuna and its tributaries is not just an environmental obligation; it’s essential for ensuring food security, biodiversity conservation, and cultural preservation in the heart of India. Integrated river basin management, more vigorous policy enforcement, inter-state cooperation, and active public participation are crucial steps forward.

As India progresses, the sustainable development of its river systems must remain a priority, so that future generations inherit flowing and thriving rivers.

The Yamuna River is fed by several important tributaries, including the Tons (its largest), Chambal, Sindh, Betwa, and Ken. The Hindon, Giri, Rishi Ganga, and Hanuman Ganga are contributing rivers, each adding to their vast river systems.

To remember the tributaries of the Yamuna, use the mnemonic “The CHiPS BeTGHaR”—Tons, Chambal, Hindon, Pabbar, Sindh, Betwa, Tons, Giri, Hanuman Ganga, Rishi Ganga—grouped by left and right-bank contributions.

The Yamuna River is often called a “dead river” due to extremely high pollution levels, especially in Delhi. Industrial waste, sewage, and reduced natural flow have severely depleted its oxygen levels, making it unfit for aquatic life.

The Ganga (Ganges) River is the longest river in India, stretching about 2,525 kilometers. Originating from the Gangotri Glacier in Uttarakhand, it flows through northern India and Bangladesh, playing a vital role in the country’s culture, economy, and ecology.

The Yamuna is a tributary of the Ganga because it merges with the Ganga River at Triveni Sangam in Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh. Though significant in length and volume, Yamuna flows into the Ganga, making it a secondary river system.

Authored by, Muskan Gupta

Content Curator

Muskan believes learning should feel like an adventure, not a chore. With years of experience in content creation and strategy, she specializes in educational topics, online earning opportunities, and general knowledge. She enjoys sharing her insights through blogs and articles that inform and inspire her readers. When she’s not writing, you’ll likely find her hopping between bookstores and bakeries, always in search of her next favorite read or treat.

Editor's Recommendations

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.