Quick Summary

Table of Contents

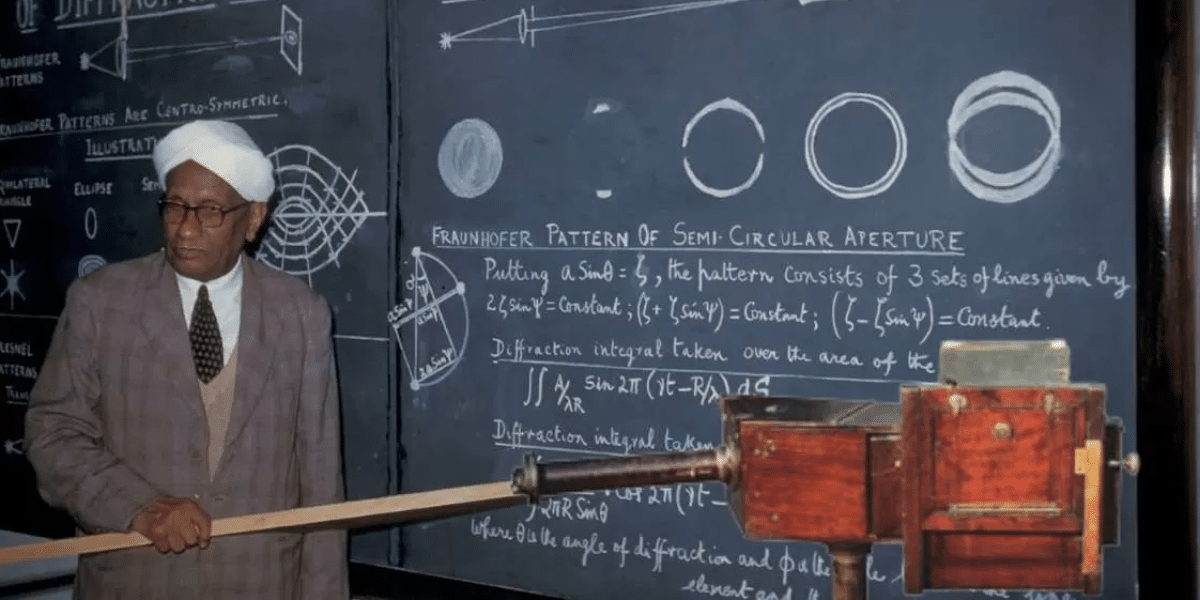

Light has always fascinated scientists because of the way it interacts with matter. One of the most remarkable discoveries in this field is the Raman Effect, which revolutionized modern spectroscopy and earned global recognition for Indian science. The phenomenon was first observed by the renowned Indian physicist Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman in 1928, while experimenting with the scattering of sunlight using simple laboratory instruments. For this groundbreaking discovery, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930, making him the first Asian scientist to receive this honor in the field of science.

The Raman Effect refers to the change in wavelength of light when molecules scatter it. Unlike ordinary scattering (Rayleigh scattering), where the wavelength remains unchanged, Raman scattering involves a shift in energy due to interactions with molecules’ vibrational and rotational modes. This effect laid the foundation for a powerful analytical technique known as Raman Spectroscopy, which is widely used in physics, chemistry, medicine, and materials science.

Today, the Raman Effect is an essential topic for students and researchers. It is also significant for UPSC and competitive exams, where questions are often framed around its principles, applications, and historical background.

The story of the Raman Effect is closely tied to the legacy of Sir C.V. Raman, one of India’s most outstanding physicists. In the early 20th century, Raman was deeply fascinated by the color of the sea and sky, and he believed that existing explanations based solely on Rayleigh scattering were incomplete. While returning from a trip to Europe in 1921, he conducted simple experiments on board a ship using prisms and filters to study the scattering of sunlight in water. These experiments sowed the seeds for what later became his most celebrated discovery.

On 28 February 1928, Raman and his student K.S. Krishnan observed a new phenomenon while passing monochromatic light through transparent liquids. They noticed that the scattered light contained additional frequencies besides the incident light. This confirmed the existence of a new type of scattering, later called the Raman Effect.

The discovery was revolutionary because it provided direct evidence of the quantum nature of light–matter interaction. Just two years later, in 1930, C.V. Raman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, making him the first Asian scientist to receive this prestigious recognition in the field of science.

The discovery not only brought global acclaim to Indian science but also inspired generations of researchers. In India, 28 February is celebrated yearly as National Science Day to commemorate this pathbreaking achievement and promote scientific curiosity among students.

The principle of the Raman Effect lies in the interaction of light with the molecules of a substance. When a beam of monochromatic light (such as laser light) passes through a medium, most of it is scattered without any change in wavelength. This is known as Rayleigh scattering. However, a small fraction of the scattered light experiences a change in wavelength due to energy exchange between the photons and the molecules of the medium. This phenomenon is called the Raman Effect.

In simple terms, when light interacts with molecules, part of its energy can be absorbed or given away to the molecular vibrational or rotational energy levels. As a result, the scattered light may appear with a frequency slightly lower (Stokes line) or higher (Anti-Stokes line) than the incident light.

The Raman Effect is significant because it provides a unique “fingerprint” of molecules. Each substance interacts differently with light, producing distinct Raman shifts that can be analyzed. This principle is the foundation of Raman Spectroscopy, a non-destructive analytical technique used in fields ranging from chemistry and physics to medicine and forensics.

Thus, the principle of the Raman Effect demonstrates how light scattering reveals molecules’ internal vibrational and rotational structure, making it one of the most powerful tools in modern science.

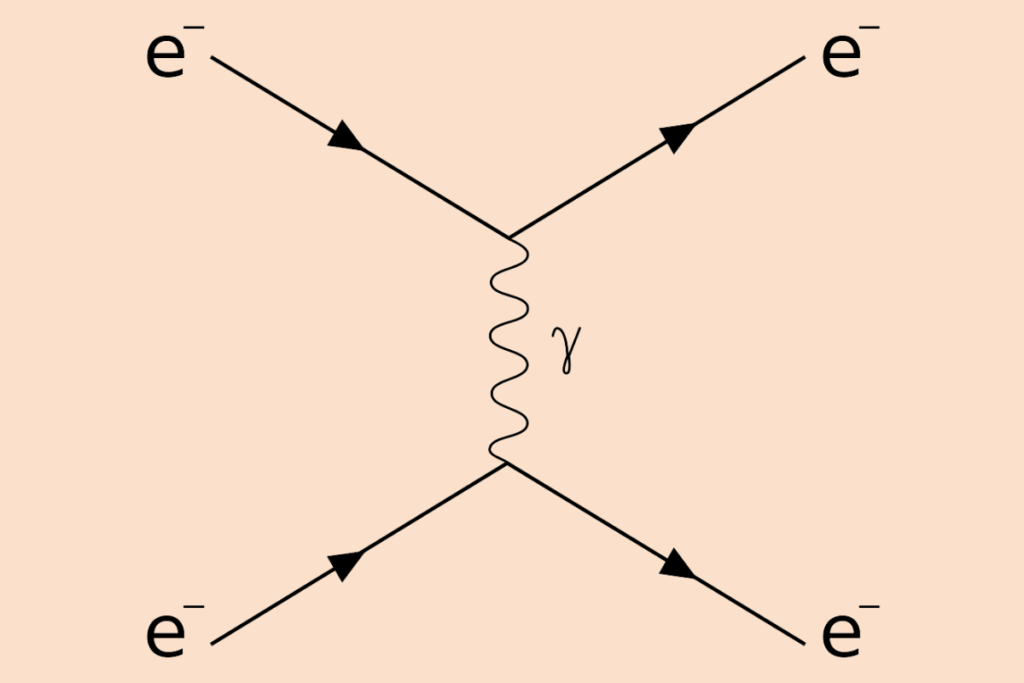

The theory of the Raman Effect can be understood using quantum mechanics concepts. When a photon of light interacts with a molecule, it can either scatter elastically (without energy change) or inelastically (with energy change). The inelastic scattering of photons produces the Raman Effect.

According to quantum theory, molecules have discrete rotational and vibrational energy levels. When light interacts with these molecules:

Mathematically(Raman Effect formula), the Raman shift (Δν) can be expressed as:

Δν=ν0−νsΔν = ν_0 – ν_sΔν=ν0−νs

Where:

The intensity of Raman scattering is much weaker than Rayleigh scattering (only about 1 in 10 million photons undergo Raman scattering), which explains why highly sensitive instruments like lasers and detectors are required to observe it.

The Raman Effect thus provides a direct method to probe molecules’ vibrational and rotational transitions. Since every molecule has unique energy levels, the Raman spectrum serves as a molecular fingerprint, making the theory not just a concept in physics but a practical tool across scientific disciplines.

The most important application of the Raman Effect is in the development of Raman Spectroscopy, a powerful technique used to study the vibrational, rotational, and other low-frequency modes of molecules. This method measures the wavelength shifts that occur when light is scattered inelastically by a substance.

In Raman Spectroscopy, a monochromatic light source, usually a laser, is directed at a sample. As the light interacts with the molecules, most photons are scattered elastically (Rayleigh scattering), but a small fraction undergoes inelastic scattering, producing Raman shifts. These shifts are recorded as a Raman spectrum containing unique peaks corresponding to the sample’s molecular structure.

Because of these features, Raman Spectroscopy is widely applied in chemistry, biology, medicine, nanotechnology, and forensic science. From identifying molecular structures to diagnosing diseases, it has become one of the most versatile tools of modern science.

Over time, researchers have developed several variants of the Raman Effect to overcome its limitations and expand its applications. Each type offers unique advantages and is suited for specific scientific or industrial purposes.

| Variant | Key Feature | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous Raman | Natural scattering | General spectroscopy |

| Resonance Raman | Enhanced by resonance | Biological pigments |

| SERS | Enhanced on metal surfaces | Trace detection, forensics |

| CARS | Nonlinear process, strong Anti-Stokes | Live-cell imaging |

| TERS | Nanometer resolution | Nanotechnology, surface analysis |

These variants have transformed the Raman Effect from a laboratory curiosity into a versatile analytical technique, making it indispensable in modern science and technology.

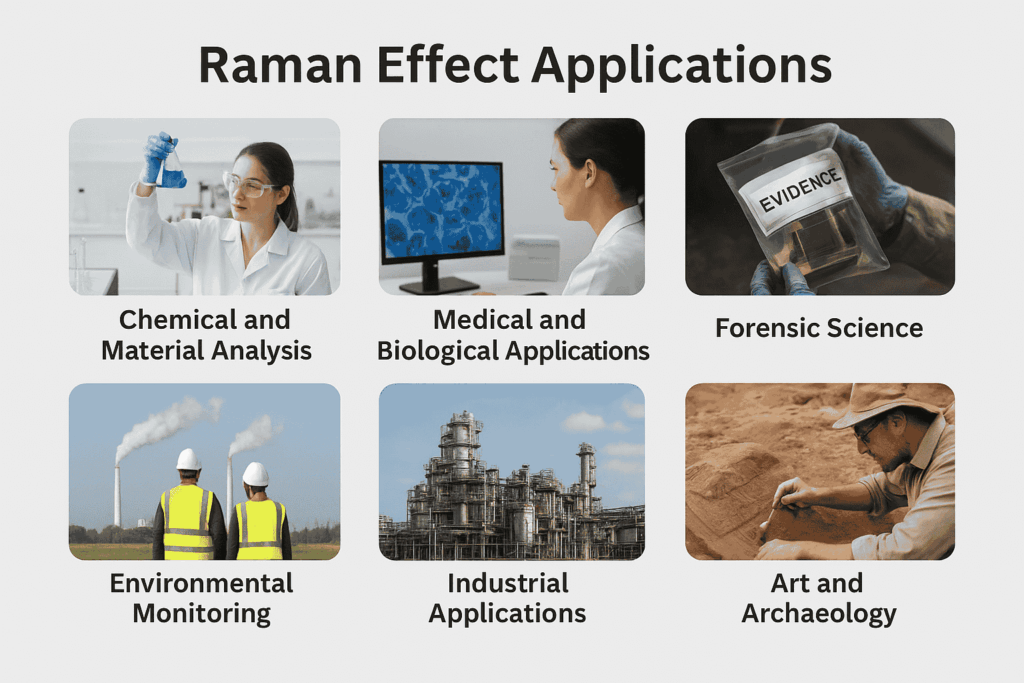

The Raman Effect has moved far beyond being a laboratory discovery and is now a powerful tool across multiple fields of science, medicine, and industry. Its ability to provide a molecular fingerprint of substances without damaging them makes it highly valuable.

| Field | Applications |

|---|---|

| Chemistry | Molecular structure, drug testing |

| Medicine | Cancer detection, live-cell imaging |

| Forensics | Explosives, drug detection |

| Environment | Pollution monitoring, microplastics |

| Industry | Semiconductors, food safety |

| Space Science | Mars exploration, mineral study |

| Art & Archaeology | Pigment identification, heritage preservation |

The Raman Effect’s versatility lies in its ability to provide fast, accurate, and non-destructive analysis, making it indispensable in research and real-world applications.

While the Raman Effect is globally significant, it also has limitations restricting its widespread use.

Despite these challenges, continuous technological advancements make Raman spectroscopy more efficient, sensitive, and accessible, ensuring its growing role in modern science.

The Raman Effect frequently appears in UPSC, SSC, State PCS, and Railway exams due to its blend of scientific importance and Indian legacy. It is connected with questions on Nobel Prize winners, physics concepts, and National Science Day (28 February).

Q. Which of the following is related to the Raman Effect?

(a) Scattering of light

(b) Radioactivity

(c) Photoelectric effect

(d) Nuclear fission

Answer: (a) Scattering of light

The Raman Effect, discovered by Sir C.V. Raman in 1928, is one of India’s most remarkable contributions to modern science. It explains how light scatters when passing through a medium, with some photons changing wavelength due to interactions with molecular vibrations. This fundamental discovery not only earned Raman the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930, making him the first Asian to receive this honor in science, but also laid the foundation for Raman Spectroscopy, a powerful analytical tool.

Today, its applications span multiple fields, including chemistry, physics, material science, medical diagnostics, forensic investigations, nanotechnology, and astronomy. Despite challenges like weak signal intensity and expensive instrumentation, its global importance remains unparalleled. In India, 28 February is celebrated as National Science Day to honor this discovery. For students and exam aspirants, the Raman Effect is a topic of both scientific and national significance.

The Raman Effect is the phenomenon where light scatters off a molecule with a change in frequency due to energy exchange with the molecule’s vibrational states. This effect, discovered by C. V. Raman, provides detailed information about molecular structure and is the basis of Raman spectroscopy.

No, the sky is not blue because of the Raman Effect—the blue color results from Rayleigh scattering, where shorter blue wavelengths scatter more than red. The Raman Effect involves frequency shifts and does not significantly affect sky color.

The Raman Effect happens when light hits something and bounces back with a tiny change in color because it shares energy with the material. It’s like a light beam giving or taking a little energy while reflecting.

The Raman principle states that when monochromatic light interacts with molecules, a small fraction of the scattered light changes frequency due to energy exchange with molecular vibrations. This frequency shift helps identify chemical structures using Raman spectroscopy.

The Raman Effect was discovered on 28th February 1928 by Sir C.V. Raman and his student K.S. Krishnan while experimenting with the scattering of sunlight.

Authored by, Muskan Gupta

Content Curator

Muskan believes learning should feel like an adventure, not a chore. With years of experience in content creation and strategy, she specializes in educational topics, online earning opportunities, and general knowledge. She enjoys sharing her insights through blogs and articles that inform and inspire her readers. When she’s not writing, you’ll likely find her hopping between bookstores and bakeries, always in search of her next favorite read or treat.

Editor's Recommendations

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.