Quick Summary

Table of Contents

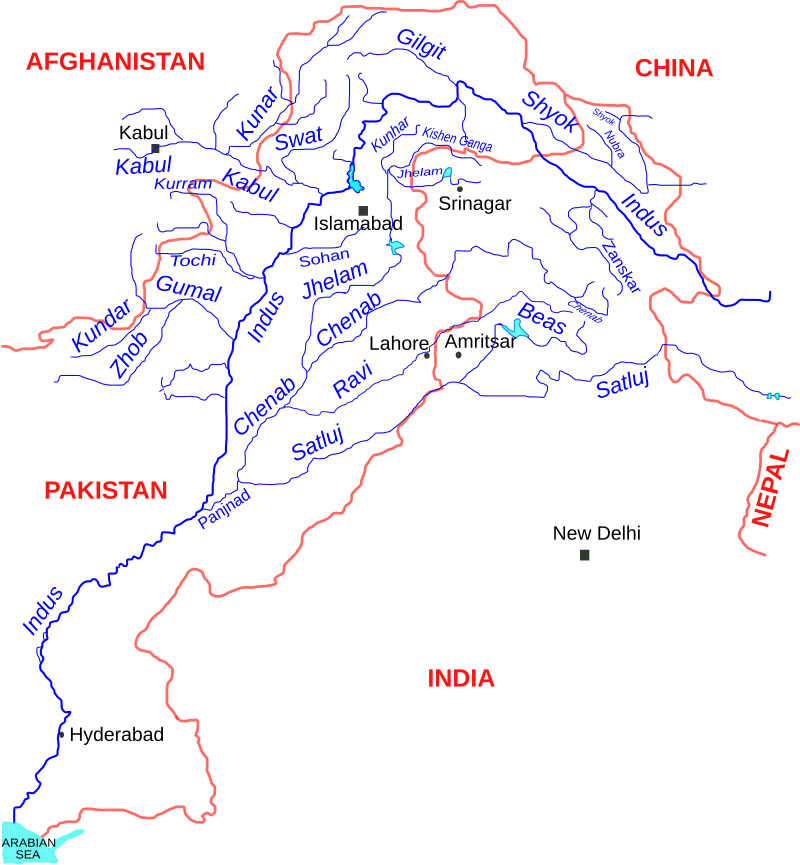

The Indus Water Treaty (IWT), signed on 19 September 1960 between India and Pakistan, is one of the most significant water-sharing agreements in the world. Brokered by the World Bank, the treaty was designed to resolve disputes over the waters of the Indus River system, which is vital for both countries’ agriculture, livelihoods, and economic stability. Under the agreement, the six rivers of the Indus basin were divided. Pakistan received control of the western rivers (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab). India was allocated the eastern rivers (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej) and limited rights over the western rivers for non-consumptive uses.

The treaty is of exceptional importance because it has largely survived decades of conflict and strained political relations between India and Pakistan. It is a rare example of successful resource sharing and continues to be a cornerstone of bilateral relations and a model of international cooperation over transboundary rivers.

The roots of the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) lie in the immediate aftermath of the Partition of India in 1947, which divided land, population, and the Indus River basin. The rivers that originated in India flowed downstream into Pakistan, making Pakistan heavily dependent on water sources controlled upstream by India. This created a situation of vulnerability and fear over water security.

Tensions escalated in April 1948, when India temporarily halted water supplies from the Ferozepur headworks to Pakistan’s canals in Punjab. This disruption affected agriculture in Pakistan and highlighted the urgent need for a long-term water-sharing arrangement. To ease tensions, a temporary Inter-Dominion Agreement (1948) was signed, under which India agreed to continue supplies in exchange for annual payments from Pakistan. However, this was only a stopgap solution and did not resolve the deeper rights issue over river waters.

By the early 1950s, the matter had become an international concern. In 1951, David E. Lilienthal, a former U.S. Tennessee Valley Authority chairman, visited the region and suggested a cooperative approach to river management. His proposal attracted the attention of the World Bank, which saw an opportunity to mediate a permanent settlement. The Bank initiated discussions between India and Pakistan, focusing on dividing river waters rather than joint management, an approach considered more practical given the political hostilities.

These negotiations, spanning almost a decade, laid the foundation for the Indus Water Treaty of 1960, which has since become a landmark in conflict resolution.

After nearly a decade of negotiations, the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) was formally signed on 19 September 1960 in Karachi, Pakistan. The signatories were Jawaharlal Nehru, the Prime Minister of India, Field Marshal Ayub Khan, the President of Pakistan, and W.A.B. Illif, representing the World Bank, which played a pivotal role in mediating and facilitating the agreement.

The treaty established a clear framework for allocating the Indus basin’s six rivers. The three eastern rivers, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej, were assigned to India, granting unrestricted consumption, irrigation, and power generation rights. Meanwhile, the three western rivers, Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab, were reserved for Pakistan, ensuring the bulk of the water supply for its agrarian economy. India, however, was permitted limited, non-consumptive use of the western rivers for activities such as hydropower, navigation, and irrigation under strict regulations.

The treaty included provisions for constructing replacement canals, dams, and storage facilities, funded through international aid and World Bank assistance, to support Pakistan’s transition and reduce its dependence on eastern rivers.

The signing of the IWT marked a rare moment of cooperation between India and Pakistan. It provided a structured solution to one of the most contentious issues post-Partition and laid the groundwork for long-term water management in the region.

| Signatory | Role | Country/Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Jawaharlal Nehru | Prime Minister | India |

| Field Marshal Ayub Khan | President | Pakistan |

| W.A.B. Illif | Vice President, World Bank (Witness) | World Bank |

The Indus Water Treaty (1960) laid out a comprehensive framework to regulate the sharing and usage of the Indus basin’s six rivers, balancing the water needs of both India and Pakistan. Its key provisions include:

To help Pakistan adjust to losing the eastern rivers, the treaty provided financial assistance (mainly through the World Bank and international donors) for building replacement works, canals, dams, and storage facilities, including the Mangla and Tarbela Dams.

A bilateral commission was established with one commissioner from each country. The PIC is a regular communication channel that exchanges data on river flows and projects and meets annually to resolve technical issues.

The treaty created a three-tiered dispute settlement system:

These provisions ensured a clear division of waters, technical cooperation, and structured conflict resolution, making the IWT one of the most resilient water treaties in the world.

Despite its success, the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) has witnessed several disputes arising from India’s projects on the western rivers, which Pakistan often perceives as violations of the treaty. Some of the most notable cases include:

Pakistan contested the Baglihar hydroelectric project on the Chenab River in Jammu and Kashmir, arguing that India’s dam design violated the treaty by allowing excessive storage. The matter was referred to a Neutral Expert appointed through the World Bank. In 2007, the Neutral Expert ruled primarily in India’s favor, permitting the project with minor modifications to the spillway design. This ruling reinforced India’s rights under the treaty to construct run-of-the-river projects with specific technical safeguards.

Pakistan challenged India’s Kishanganga hydroelectric project on a tributary of the Jhelum, claiming it would reduce downstream water flow into Pakistan’s Neelum-Jhelum project. The case went to the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague, which ruled in 2013 that India could divert water for power generation, provided it maintained a minimum flow downstream. This was seen as a balanced decision, protecting both countries’ interests.

The Ratle hydroelectric project on the Chenab River has faced repeated objections from Pakistan over design concerns. Islamabad contends that India’s plans allow excessive drawdown capacity, potentially violating the IWT. The dispute remains unresolved, with Pakistan seeking international arbitration and India defending its compliance with treaty provisions.

India proposed the Tulbul Navigation Project (also called the Wullar Barrage) on the Jhelum River to regulate water levels for navigation. Pakistan opposed it, alleging it could give India control over downstream flows. Since the 1980s, the project has been stalled due to Pakistani objections, symbolizing the deep mistrust between the two sides.

These disputes highlight the sensitivity of water issues in India–Pakistan relations. While the IWT has provided institutional mechanisms to manage disagreements, Pakistan’s frequent objections reflect concerns over its dependence on Western rivers. Hydroelectric projects are critical for India’s energy needs in Jammu and Kashmir. Each dispute revives debates about the treaty’s fairness. Yet, both countries adhere to the IWT even during wars and political crises, underscoring its resilience as a conflict-management tool.

| Project/Dispute | River | Pakistan’s Objection | Verdict/Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baglihar Dam (2005–07) | Chenab | Excessive storage & dam design violations | Neutral Expert allowed project with minor changes |

| Kishanganga Project (2010–13) | Jhelum tributary | Diversion reduces flow into Neelum-Jhelum project | PCA allowed diversion; minimum flow to Pakistan required |

| Ratle Project (Ongoing) | Chenab | Excessive drawdown & design concerns | Dispute unresolved; arbitration in progress |

| Tulbul Navigation Project | Jhelum | Control over downstream flow | The project has been stalled since the 1980s |

The Indus Water Treaty (IWT) is widely regarded as one of the most successful examples of global transboundary water sharing. Its most tremendous significance lies in its endurance for over six decades, despite repeated hostilities and even full-scale wars between India and Pakistan (1965, 1971, and 1999). At a time when political relations have often been strained, the treaty has ensured a consistent framework of cooperation, preventing water from becoming a trigger for armed conflict.

For Pakistan, which relies on the Indus and its western tributaries for more than 80% of its agriculture, the treaty guarantees a predictable water supply essential for irrigation, drinking water, and food security. For India, the treaty secures complete control over the eastern rivers while permitting carefully defined use of the western rivers, enabling the development of hydropower projects and irrigation systems in Jammu & Kashmir.

Globally, the IWT is seen as a model for international water diplomacy. It demonstrates how even bitter rivals can cooperate on critical resources when guided by clear rules, third-party mediation, and robust dispute resolution mechanisms. Its resilience makes it a landmark in international law and a cornerstone of South Asian water management.

While the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) is praised globally, it has faced sustained criticism and challenges over the decades.

Many Indian analysts argue that the treaty disproportionately favors Pakistan, as it controls nearly 80% of the Indus basin waters. Despite being the upstream state with a larger technological capacity, India has limited rights on the western rivers, restricting its potential for irrigation and hydropower development.

India and Pakistan face growing populations and expanding agricultural needs, with sharply increasing water demand. The treaty, framed in 1960, does not account for modern requirements such as urban water supply, industrial use, or environmental flows.

The Indus basin is highly dependent on Himalayan glaciers and snowmelt. Accelerated glacier retreat due to climate change will likely cause unpredictable flood flows in the short term and water scarcity in the long term. The treaty, however, lacks provisions to address climate-related variability and adaptation.

Frequent disputes over India’s hydroelectric projects, such as Baglihar, Kishanganga, and Ratle, reflect deep mistrust. Pakistan often views Indian projects as attempts to manipulate flows, while India insists on its treaty-compliant rights. These recurring disagreements strain bilateral relations and highlight ambiguities in technical clauses.

In short, while the IWT has prevented major water wars, its limitations in scope and outdated framework pose significant challenges for the future, demanding modernization and cooperative adaptation to new realities.

In January 2023, India issued a formal notice to Pakistan invoking Article XII(3) of the Indus Waters Treaty, calling for renegotiation of the 1960 agreement due to “fundamental changes in circumstances” such as demographic shifts, climate change, and implementation challenges.

In August 2024, India served another notice seeking a review and modification of the treaty. At the same time, New Delhi announced the suspension of meetings of the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC) until Islamabad agreed to engage in renegotiations. Pakistan strongly opposed these moves, maintaining that India cannot unilaterally alter the treaty.

Meanwhile, arbitration proceedings continued through the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) and the Neutral Expert channel. The PCA has been addressing issues related to treaty interpretation and India’s hydropower projects on the western rivers. At the same time, the Neutral Expert process initiated in 2022 remains engaged with technical disagreements over dam design and operation.

Due to the suspension of PIC meetings, the routine exchange of hydrological data and consultations on new projects have been disrupted. These developments signal a period of heightened geopolitical tension and represent one of the most serious challenges to the durability of the Indus Water Treaty since its signing in 1960.

Though resilient for over six decades, the Indus Water Treaty increasingly shows its limitations in addressing modern challenges. With climate change, glacial retreat, and erratic monsoon patterns threatening the Indus basin’s stability, India and Pakistan need to move beyond disputes and explore avenues for cooperative adaptation.

Modernizing the treaty could involve expanding its scope to include environmental flows, groundwater management, flood control, and data-sharing on climate impacts. Joint initiatives on hydropower, irrigation efficiency, and basin-wide conservation projects could transform water into a medium of cooperation rather than conflict.

Amendments may also be required to update technical provisions, clarify ambiguities, and establish more flexible dispute resolution mechanisms. Ultimately, the treaty’s survival depends on both nations’ political will to prioritize long-term water security over short-term rivalry.

| Eastern Rivers (India) | Western Rivers (Pakistan) |

|---|---|

| Ravi | Indus |

| Beas | Jhelum |

| Sutlej | Chenab |

The Indus Water Treaty (1960) remains a cornerstone of water diplomacy between India and Pakistan, symbolizing how cooperation can endure amid strained relations. By dividing the rivers and providing mechanisms for dispute resolution, the treaty has helped prevent water conflicts from escalating into larger confrontations. Despite wars, cross-border tensions, and decades of mistrust, the agreement continues to function, making it one of the world’s most resilient water-sharing arrangements.

However, modern challenges such as climate change, rising populations, rapid urbanization, and new hydro projects demand that the treaty evolve. Both nations must embrace joint projects, better data sharing, and climate adaptation measures to ensure sustainable use of the Indus basin. Strengthening cooperation rather than confrontation will secure water resources and contribute to regional stability. The treaty’s future success will depend on flexibility, trust-building, and adapting to the changing geopolitical and environmental realities.

Read more:

Longest River in India

The Indus Water Treaty is a water-sharing agreement signed in 1960 between India and Pakistan, brokered by the World Bank. It allocates control of six rivers in the Indus River system. India gets the eastern rivers (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej) while Pakistan controls the western rivers (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab).

The Indus Water Treaty of 1960 is often criticized as a major misstep by former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who was accused of prioritizing personal ambitions over national interest.

Under the 1960 Indus Water Treaty, India has full rights over the eastern rivers (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej) and limited non-consumptive use of the western rivers (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab), while ensuring their unrestricted flow to Pakistan for irrigation and other needs.

The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) was signed on 19 September 1960 in Karachi, Pakistan, by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistani President Ayub Khan. The World Bank acted as mediator for the water-sharing agreement.

On 23 April 2025, in response to a terrorist attack near Pahalgam, Kashmir, the Government of India announced the suspension of the treaty with Pakistan, citing national security concerns.

Authored by, Muskan Gupta

Content Curator

Muskan believes learning should feel like an adventure, not a chore. With years of experience in content creation and strategy, she specializes in educational topics, online earning opportunities, and general knowledge. She enjoys sharing her insights through blogs and articles that inform and inspire her readers. When she’s not writing, you’ll likely find her hopping between bookstores and bakeries, always in search of her next favorite read or treat.

Editor's Recommendations

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.