Quick Summary

Table of Contents

The Harappan Civilization, also known as the Indus Valley Civilization, was a Bronze Age society and one of the world’s three earliest civilizations, alongside Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. Flourishing between 3300 BCE and 1300 BCE in northwestern South Asia, it is renowned for its advanced urban planning, sophisticated drainage systems, and undeciphered script. This article provides a comprehensive introduction to the Harappan Civilization, exploring its history, major cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, cultural achievements, and the mysteries surrounding its decline. It is an essential resource for students, UPSC/SSC aspirants, and history enthusiasts.

We will journey through the meticulously laid streets of its cities, decipher the secrets held by its seals, unravel the mysteries of its citadel of Harappan civilization, and contemplate the various theories surrounding the decline of Harappan civilization. By exploring its art, technology, and trade networks, we aim to construct a vivid picture of a civilization that was, in many ways, millennia ahead of its time.

Before we delve into the details, it is crucial to answer a fundamental question: what is Harappan civilization? Also known as the Indus Valley Civilization, it was one of the world’s three earliest urban cultures, alongside ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Thriving during the Harappan civilization time period of approximately 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE, it represented the mature, urban phase of a longer cultural tradition in the Indus River basin.

Its name is derived from Harappa, the first site excavated in the early 20th century. This civilization was distinguished by its remarkable uniformity and standardization across a vast geographical expanse. From the type of bricks used in construction to the systems of weights and measures, a surprising degree of homogeneity is evident across all major sites, suggesting strong central administration or a shared cultural ethos. It was a society that mastered urban living, with unparalleled expertise in town planning of the Harappan civilization, drainage systems, and water management, creating a template for urban efficiency that would not be seen again for centuries.

The story of the Harappan Civilization’s discovery is a tale of archaeological curiosity and persistence. For centuries, the ruins lay buried under the silt of the Indus plains, their significance unknown. The first clues emerged in the mid-19th century when British engineers building the railway line in Punjab used bricks from a massive mound near the village of Harappa as ballast. Unknowingly, they were plundering the ancient city itself.

It wasn’t until 1921, under the directorship of Daya Ram Sahni, that systematic excavations began at Harappa. The following year, R.D. Banerjee began digging at another mound, Mohenjo-daro (meaning ‘Mound of the Dead’), further south. What they unearthed sent shockwaves through the historical community. They had not discovered just isolated towns but the remains of a vast, forgotten civilization that once rivaled its contemporaries in Egypt and Sumer. John Marshall, the then Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), was instrumental in recognizing the significance of these finds and first used the term ‘Indus Valley Civilization’.

Subsequent excavations by luminaries like Mortimer Wheeler, George Dales, and numerous Indian archaeologists have continued to expand our understanding, revealing hundreds of sites and painting a richer picture of this ancient culture.

Understanding the Harappan civilization time period is key to contextualizing its achievements. Scholars typically divide its evolution into three main phases:

| Period | Approximate Time Frame | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Harappan | 7000 – 3300 BCE | Early Neolithic villages; beginnings of agriculture and pottery. |

| Early Harappan | 3300 – 2600 BCE | Development of trade networks; emergence of small towns. |

| Mature Harappan | 2600 – 1900 BCE | Peak urban phase; planned cities, standardization, writing, vast trade. |

| Late Harappan | 1900 – 1300 BCE | Decline of urbanism; abandonment of cities; migration eastward. |

| Post-Harappan | 1300 BCE onwards | Rise of regional cultures like the Painted Grey Ware culture. |

The sheer size of the Harappan Civilization is staggering. At its peak, it encompassed over a million square kilometers, far exceeding the geographical spread of contemporary ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia combined. To visualize this vastness, a Harappan civilization map would show its core centered along the Indus River in modern-day Pakistan, but its influence stretched far beyond.

This expansive territory was dotted with over 1,000 sites, including five major urban centers.

A Harappan civilization map illustrates a network of cities, towns, and villages connected by trade routes, both overland and riverine, forming a cohesive economic and cultural zone.

The most striking feature of the Mature Harappan phase is its extraordinary town planning of Harappan civilization. This urban brilliance sets it apart from all other contemporary cultures and speaks volumes about its advanced administrative and engineering capabilities.

Almost all major urban centers were divided into two distinct parts: the Citadel of Harappan civilization and the Lower Town.

The cities were built on a strict grid pattern oriented along the cardinal directions (north-south, east-west). The streets were wide, straight, and intersected at right angles, dividing the city into large rectangular blocks. This design facilitated not only organization but also airflow and movement.

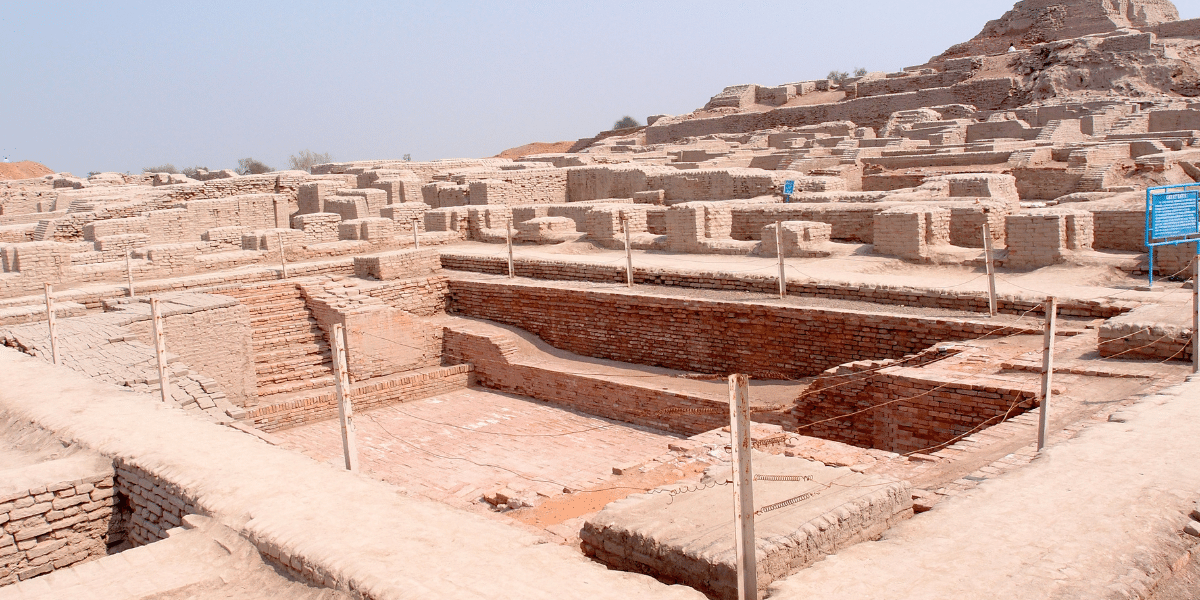

The Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro is one of the most celebrated structures of the ancient world. Located within the citadel, it is a large, waterproofed pool made of finely baked bricks and gypsum mortar. It was surrounded by corridors and rooms and likely served a ritual, religious purpose, indicating the importance of purification ceremonies.

Perhaps the most impressive feat of town planning of Harappan civilization was its sophisticated, city-wide drainage system. It was far more advanced than any found in contemporary Middle Eastern sites.

Houses, ranging from single-room tenements to large mansions with dozens of rooms, were built around courtyards. They were made of standardized, kiln-baked bricks of a uniform ratio (4:2:1). This standardization across a vast region is a unique feature, pointing to a centralized authority or a deeply ingrained cultural standard. Most houses had wells, providing direct access to clean water.

Deciphering the social structure of the Harappans is challenging due to the lack of deciphered written records. However, material evidence provides crucial clues.

The Harappan economy was a complex and thriving system based on a surplus of agricultural production, which supported urbanization and fueled extensive trade networks.

The fertile plains of the Indus and its tributaries provided the ideal conditions for agriculture. They grew a variety of crops:

They used wooden ploughs and stone sickle blades for cultivation. Canals were dug for irrigation, and sophisticated water storage systems, as seen in Dholavira, were constructed to manage water resources.

They domesticated a range of animals, including cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats, pigs, and cats. The humped zebu bull was particularly common and is frequently depicted on the seals of Harappan civilization. They also used elephants and camels, and evidence suggests they may have domesticated fowl.

The Harappans were master traders, maintaining extensive networks.

Harappan cities were hubs of industrial activity.

Understanding Harappan religion is speculative, as no temples or definitive religious texts have been found. Interpretations are based on seals, figurines, and structural remains.

One of the greatest enigmas of the Harappan Civilization is its writing system. The seals of Harappan civilization are its most famous artifacts, but their message remains locked away.

Typically made of steatite (a soft stone that was baked to harden), these small, square seals are beautifully carved. They feature a line of script at the top and a central depiction of an animal, the unicorn being the most common, but also bulls, elephants, rhinoceroses, and tigers. The back has a perforated knob for suspension. As mentioned, their primary use was probably in trade for stamping goods. The artistic quality of these seals of Harappan civilization remains unmatched in the ancient world for their miniature detail.

The Harappan script remains undeciphered, posing a massive challenge to understanding this culture more deeply.

The language(s) spoken by the Harappans is a subject of intense debate. Various hypotheses suggest it could be a precursor to:

Until the script is deciphered, the language and much of the civilization’s intellectual life will remain a mystery.

Despite the focus on utilitarian objects, the Harappans produced a rich variety of art, displaying skill, observation, and a sense of aesthetics.

The decline of Harappan civilization around 1900 BCE was not a sudden, catastrophic event but a gradual process of de-urbanization that unfolded over centuries. No single cause can explain it; rather, it was likely a combination of several factors.

In essence, a combination of ecological stress and economic breakdown likely led to the abandonment of the great cities. The population did not vanish; they dispersed into smaller, rural villages in the east and south, gradually merging with other cultures and giving rise to the subsequent cultural phases of the Indian subcontinent. The story of the decline of Harappan civilization is a complex narrative of environmental and social transformation.

The Harappan Civilization left an indelible mark on the cultural fabric of the Indian subcontinent. While its script was forgotten and its cities buried, its legacy lived on in subtle ways.

The Harappan Civilization stands as a monument to human innovation and organization. For seven centuries, it built and sustained a vast, peaceful, and highly sophisticated urban world. Its achievements in town planning, sanitation, and trade are a source of wonder. Yet, it remains an enigma, its voice silent behind the veil of an undeciphered script. The mystery of its uniform culture and its gradual decline continues to fuel research and debate. As excavations and scientific analyses continue, particularly at sites like Rakhigarhi, we inch closer to understanding the full story of this remarkable chapter in human history, a story that fundamentally shaped the destiny of the Indian subcontinent.

Read More:-

The Harappan Civilization, also known as the Indus Valley Civilization (3300–1300 BCE), was one of the world’s earliest urban cultures. Centered in present-day India and Pakistan, it was renowned for its advanced city planning, well-structured drainage systems, flourishing trade, agriculture, and distinctive art and crafts. Major sites like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro showcase its cultural brilliance, making it a foundation of ancient Indian history.

The Harappan culture created the earliest precise system of regulated weights and measures, sometimes called the Indus River Valley culture; some of its measurements were as precise as 1.6 mm. Terracotta, metal, and stone were among the materials used by the Harappans to produce jewelry, sculptures, and seals.

The Harappa Civilization was discovered in 1921 by Daya Ram Sahni, an Indian archaeologist, during excavations at Harappa in present-day Punjab, Pakistan. This discovery, followed by R.D. Banerjee’s excavation at Mohenjo-daro in 1922, revealed the existence of the Indus Valley Civilization one of the world’s earliest urban cultures known for advanced city planning, trade, and art.

First discovered in 1921 in the Punjab region at Harappa, the civilization was later found in 1922 in the Sindh (Sind) region at Mohenjo-daro (Mohenjodaro), close to the Indus River.

The Harappan Civilization, or Indus Valley Civilization, is divided into three phases: the Early Harappan Phase (3300–2600 BCE), the Mature Harappan Phase (2600–1900 BCE), and the Late Harappan Phase (1900–1300 BCE).

The decline of the Harappan Civilization is attributed to climate change, shifting river patterns, declining trade, overexploitation of resources, and possibly invasions, which led to urban collapse and population dispersal.

Authored by, Muskan Gupta

Content Curator

Muskan believes learning should feel like an adventure, not a chore. With years of experience in content creation and strategy, she specializes in educational topics, online earning opportunities, and general knowledge. She enjoys sharing her insights through blogs and articles that inform and inspire her readers. When she’s not writing, you’ll likely find her hopping between bookstores and bakeries, always in search of her next favorite read or treat.

Editor's Recommendations

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.