Quick Summary

Table of Contents

Classical Dance of India refers to a group of traditional dance forms that the Sangeet Natak Akademi, the national academy for music, dance, and drama, formally recognizes. These art forms trace their roots to the ancient Natya Shastra, a Sanskrit text on performing arts, which outlines the principles of dance, drama, and music. A hallmark of Indian classical dance is its unique blend of abhinaya (expression), nritta (pure dance), geet (music), and tala (rhythm). Each performance is not just entertainment but a profound form of storytelling, often based on themes from mythology, epics, and spiritual traditions.

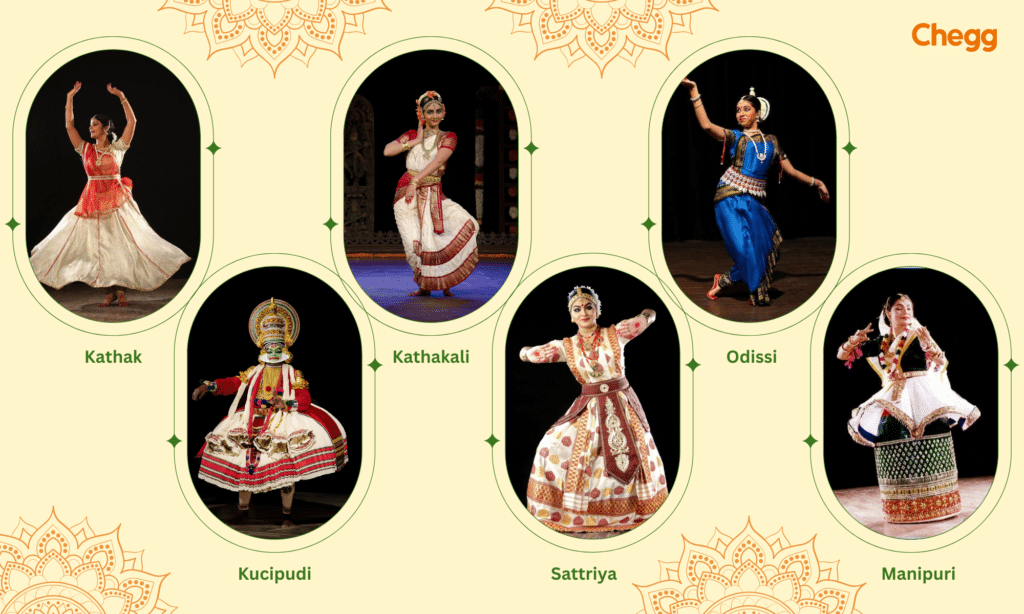

Deeply interwoven with Indian culture, classical dances are performed during religious rituals, temple festivals, and cultural celebrations, serving as a medium to preserve and pass down traditions across generations. Officially, there are eight recognized classical dances of India: Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Kathakali, Kuchipudi, Manipuri, Mohiniyattam, Odissi, and Sattriya. Some scholars and practitioners also include Chhau, bringing the count to nine and highlighting the richness and diversity of India’s performing arts heritage.

The origin of classical dance in India is deeply rooted in the Natya Shastra, an ancient Sanskrit text composed by Bharatamuni around 200 BCE–200 CE. This treatise laid down the principles of dance, drama, and music, describing movement, gestures, expressions, and rhythm to convey emotions and spiritual ideas. Classical dance, therefore, was never just an art form but a holistic medium of worship, storytelling, and education.

In its early phase, classical dance flourished within temples, where it was performed as an offering to deities. Dancers, often known as Devadasis, enacted episodes from epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata, bringing sacred stories to life through abhinaya (expressions) and rhythmic patterns. These performances symbolized devotion, making dance integral to spiritual practice and community life.

However, classical dance declined during the medieval and colonial periods due to the fall of temple patronage, suppression under foreign rule, and social stigma attached to performers. Many traditions risked fading away as they lost their sacred spaces and cultural recognition.

The revival of classical dance began in the early 20th century, when scholars, artists, and cultural institutions like the Sangeet Natak Akademi and Kalakshetra worked to restore its dignity. Legendary exponents such as Rukmini Devi Arundale (Bharatanatyam), Birju Maharaj (Kathak), and Kelucharan Mohapatra (Odissi) played a crucial role in re-establishing classical dance as a respected art form, both in India and globally. Today, these dances continue to evolve while retaining their ancient essence.

India’s classical dances are artistic expressions and living traditions that preserve stories, rituals, and philosophies. Recognized by the Sangeet Natak Akademi, these forms reflect different regions’ spiritual and cultural essence.

Bharatanatyam is one of the oldest classical dances, dating back over 2,000 years, and originated in Tamil Nadu’s temples. Known for its fixed upper torso, rhythmic footwork, and graceful mudras, it expresses devotion and storytelling through abhinaya. Costumes include pleated silk sarees, temple jewelry, and expressive makeup.

Performed to Carnatic music, the themes revolve around Lord Shiva (as Nataraja), Vishnu, and divine love. Revived in the 20th century by Rukmini Devi Arundale, it is now performed worldwide. Other eminent exponents include Padma Subrahmanyam, Yamini Krishnamurthy, and Alarmel Valli.

Kathak, meaning “storyteller,” originated in North India, particularly Uttar Pradesh. Rooted in temple storytelling traditions, it later flourished in Mughal courts, blending Hindu devotional themes with Persian elegance. Known for its fast spins, intricate footwork, rhythmic patterns, and graceful abhinaya, Kathak uses instruments like tabla, sarangi, and harmonium with Hindustani music.

Costumes include anarkali-style dresses or lehengas for women and angarkhas or churidars for men. Themes depict Radha-Krishna tales, Bhakti poetry, and Mughal court romances. Legendary exponents include Birju Maharaj, Sitara Devi, and Kumudini Lakhia, who popularized Kathak globally.

Kathakali, from Kerala, is a dance-drama known for its grand makeup, elaborate costumes, and dramatic storytelling. Emerging in the 17th century, it portrays mythological tales from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Puranas. Performers use exaggerated facial expressions, hand gestures, and vigorous movements, accompanied by drums like chenda and maddalam.

Costumes feature colorful headgear, ornate attire, and painted faces, each color symbolizing character traits (green for heroes, red for villains). Traditionally performed overnight in temples and courtyards, Kathakali is one of India’s most visually striking art forms. Renowned masters include Kalamandalam Gopi and Kottakkal Sivaraman.

Kuchipudi originated in Andhra Pradesh as a temple dance dedicated to Lord Krishna. Traditionally performed by male Brahmin troupes, it later evolved into a stage art embraced by both men and women. Known for its graceful footwork, rhythmic patterns, and expressive abhinaya, Kuchipudi often blends dance with theatrical elements.

Dancers wear lightweight costumes similar to Bharatanatyam, with expressive jewelry and makeup. Music follows the Carnatic style, using mridangam, flute, and violin. Popular themes include episodes from Krishna’s life and devotional poetry. Notable exponents include Vempati Chinna Satyam, Raja Reddy, and Radha Reddy.

Manipuri is profoundly spiritual and devotional from the northeastern state of Manipur. Rooted in Vaishnavism, it centers around stories of Radha and Krishna, particularly the Ras Lila. Known for its soft, graceful movements and circular patterns, it contrasts with the vigorous style of other dances.

Women wear unique costumes, including embroidered cylindrical skirts (potloi), translucent veils, and light jewelry, while men often dress as Krishna or cowherds. Music is devotional, accompanied by instruments like pung (drum) and cymbals. Notable exponents include Guru Bipin Singh, Jhaveri Sisters, and Rajkumar Singhajit Singh, who brought Manipuri to national prominence.

Odissi, Odisha’s classical dance, is among the oldest surviving forms, evidenced by ancient temple sculptures. Traditionally performed as an offering to Lord Jagannath, it combines fluid torso movements, tribhangi (three-body bends), and intricate gestures. Costumes include brightly colored silk sarees with silver jewelry and elaborate headpieces.

The music is based on Odissi classical ragas, using instruments like mardala and flute. Themes often portray episodes from Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda, focusing on Radha-Krishna devotion. Revived in the 20th century by Kelucharan Mohapatra, Odissi has gained global recognition. Eminent dancers include Sonal Mansingh and Sanjukta Panigrahi.

Mohiniyattam, meaning “dance of the enchantress,” is a graceful form from Kerala. Performed traditionally by women, it embodies feminine grace through soft movements, swaying steps, and gentle abhinaya. The costume includes a white kasavu saree with golden borders, minimal jewelry, and natural makeup with a bun adorned by jasmine flowers.

The music follows the Carnatic tradition, often accompanied by mridangam, veena, and edakka. Themes generally revolve around devotion to Lord Vishnu or expressions of love and separation (sringara rasa). Revived by Vallathol Narayana Menon and enriched by exponents like Kalamandalam Kalyanikutty Amma, Mohiniyattam is celebrated worldwide.

Sattriya, from Assam, was introduced in the 15th century by the saint Srimanta Sankardeva as a form of devotion in Vaishnavite monasteries (sattras). Initially performed by monks as a medium for spiritual storytelling, it later evolved into a respected classical dance. Known for its rhythmic footwork, devotional abhinaya, and combination of dance and drama, Sattriya depicts stories of Krishna and Vishnu.

Costumes include traditional Assamese attire like pat silk dhotis, chadors, and jewelry. Music is based on Borgeet (devotional songs) accompanied by khol, flute, and cymbals. Eminent exponents include Guru Jatin Goswami and Indira PP Bora.

Chhau, debated as the ninth classical dance, is practiced in Odisha, Jharkhand, and West Bengal. It blends folk, martial, and classical elements and is often performed during festivals. Known for its vigorous jumps, martial movements, and masked expressions, Chhau portrays themes from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and local folklore. Costumes vary; some forms use elaborate masks, while others rely on facial expressions.

The music, dominated by drums like dhol and dhamsa, creates a powerful rhythm. Though semi-classical, the Sangeet Natak Akademi recognizes it as a significant cultural tradition. Notable gurus include Gambhir Singh Mura and Padma Shri Shashadhar Acharya.

| Dance | State | Costume/Makeup | Music | Key Features | Famous Exponents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bharatanatyam | Tamil Nadu | Silk saree, temple jewelry, eye makeup | Carnatic | Fixed torso, footwork, abhinaya | Rukmini Devi Arundale, Alarmel Valli |

| Kathak | UP/North | Anarkali/lehengas, churidar, light makeup | Hindustani | Spins, rhythmic footwork, storytelling | Birju Maharaj, Sitara Devi |

| Kathakali | Kerala | Headgear, painted face, colorful attire | Chenda, Maddalam | Dramatic gestures, myth stories | Kalamandalam Gopi, Kottakkal Sivaraman |

| Kuchipudi | Andhra | Lightweight saree, jewelry, minimal makeup | Carnatic | Graceful steps, abhinaya, dance-drama | Vempati Chinna Satyam, Radha Reddy |

| Manipuri | Manipur | Potloi skirt, veil, light jewelry | Pung, cymbals | Soft, circular movements, devotional | Guru Bipin Singh, Rajkumar Singhajit |

| Odissi | Odisha | Silk saree, silver jewelry, headpiece | Odissi Classical | Fluid torso, tribhangi, storytelling | Kelucharan Mohapatra, Sonal Mansingh |

| Mohiniyattam | Kerala | White kasavu saree, minimal jewelry, bun | Carnatic | Gentle swaying, feminine grace | Kalamandalam Kalyanikutty Amma |

| Sattriya | Assam | Pat silk dhoti/chador, Assamese jewelry | Borgeet | Rhythmic steps, devotional storytelling | Guru Jatin Goswami, Indira PP Bora |

| Chhau (Opt.) | Odisha/JH/WB | Masked/colorful attire | Dhol, Dhamsa | Martial jumps, folk-myth stories | Gambhir Singh Mura, Shashadhar Acharya |

Indian classical dances are timeless art forms that blend devotion, storytelling, music, and rhythm. They reflect the country’s rich cultural, spiritual, and artistic heritage. Beyond entertainment, these dances serve as a medium to preserve centuries-old traditions, mythology, and moral values, passing them on to future generations.

Classical dances are deeply intertwined with spirituality, often performed as offerings to deities in temples and sacred spaces. Rooted in the Natya Shastra, they bring epic tales from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Puranas to life through abhinaya (expressions), gestures, and rhythmic movements. Each posture and mudra conveys meaning, allowing dancers to narrate stories of devotion, heroism, love, and moral lessons, preserving India’s literary and religious heritage.

Historically, these dances were integral to festivals, temple rituals, and religious ceremonies. Forms like Bharatanatyam, Kathakali, Manipuri, and Odissi strengthened community bonds, celebrated seasonal and spiritual occasions, and connected audiences with divine narratives. Performances created a sacred interaction between the dancer, deity, and spectators, ensuring cultural continuity.

In contemporary times, classical dance has become a tool of cultural diplomacy. Institutions and renowned dancers showcase these art forms worldwide, from international festivals to online platforms, promoting India’s rich heritage. Their global reach enhances India’s soft power, demonstrating its artistic excellence, devotion, and cultural depth. By preserving and promoting classical dances, India continues celebrating its spiritual and cultural essence, inspiring audiences worldwide.

Classical dance in India continues to thrive, evolving with modern platforms while preserving its spiritual, cultural, and artistic essence. These dances remain a living tradition, connecting performers and audiences to centuries-old stories, mythology, and devotional practices.

Organizations such as the Sangeet Natak Akademi, universities, and renowned dance schools play a crucial role in sustaining classical dance. They offer formal training programs, document traditional techniques, and conduct workshops, performances, and festivals. This structured support ensures that the art forms are passed on to new generations with authenticity and integrity.

Government bodies, including the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) and the Ministry of Culture, provide grants, scholarships, and nationwide schemes to support dancers, cultural events, and research. These initiatives help sustain the art forms financially and culturally, creating opportunities for performers and audiences to engage with India’s rich dance heritage.

The advent of digital technology has significantly increased the visibility of classical dance. Platforms like YouTube, online classes, and international cultural festivals allow dancers to reach global audiences, promoting cross-cultural learning and appreciation. Classical dance is no longer confined to temple courtyards or auditoriums; it thrives on digital and international stages.

Despite these efforts, classical dance faces challenges such as commercialization, dwindling student interest, and the struggle to maintain traditional purity while appealing to contemporary audiences. Continuous institutional, governmental, and community support is vital to preserving these invaluable art forms for future generations.

Indian classical dances embody the country’s diverse cultural, spiritual, and artistic heritage. Each form, whether it is the intricate footwork and storytelling of Kathak, the graceful swaying movements of Mohiniyattam, the sculptural poses of Bharatanatyam, or the dramatic expressions of Kathakali, reflects centuries of tradition, devotion, and mythology. Through these dances, India preserves its rich history, literary treasures, and aesthetic values while providing a powerful medium for storytelling, emotional expression, and spiritual connection.

The preservation and promotion of these classical dances are essential to maintaining cultural continuity and projecting India’s soft power worldwide. Institutions like the Sangeet Natak Akademi, universities, dedicated dance schools, government initiatives from the Ministry of Culture, and organizations like IGNCA are pivotal in nurturing talent and sustaining tradition. Modern platforms, including online classes, YouTube, and global cultural festivals, further expand their reach. Supporting these art forms ensures that the spiritual depth, creativity, and timeless artistry of Indian classical dance continue to inspire audiences both in India and across the world.

Read More:-

India is home to 8 major classical dance forms are Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Kathakali, Manipuri, Odissi, Mohiniyattam, Sattriya, and Kuchipudi. Each dance form reflects the rich cultural heritage, spiritual depth, and storytelling traditions of different regions across the country.

The 9 rasas are; Shringara, Roudra, Bibhatsa, Veera, Shaant, Haasya, Karuna, Bhayanak, and Adbhuta.

The oldest classical dance in India is Bharatanatyam, which originated from Tamil Nadu. It has a history of over 2,000 years and is deeply rooted in religious and cultural traditions.

Kathak is a classical dance form of India that is famous in the regions of Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Delhi.

Uday Shankar is regarded as the “Father of Modern Dance in India.” He was instrumental in blending Indian classical dance with contemporary elements, helping to bring Indian dance to international recognition.

India’s classical dances are linked to its states, but not all 29 states have a distinct classical dance. The eight officially recognized classical dances—Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Kathakali, Kuchipudi, Manipuri, Odissi, Mohiniyattam, and Sattriya—originate from specific states. In contrast, several other states feature folk or regional dance forms rather than classical ones.

The Chhau Dance is often regarded as the ninth classical dance of India and is recognized by the Ministry of Culture, although the Sangeet Natak Akademi officially lists only eight. Originating from martial, folk, and tribal traditions, Chhau is performed in Eastern India and has three distinct styles: Seraikella Chhau from Jharkhand, Mayurbhanj Chhau from Odisha, and Purulia Chhau from West Bengal.

Authored by, Muskan Gupta

Content Curator

Muskan believes learning should feel like an adventure, not a chore. With years of experience in content creation and strategy, she specializes in educational topics, online earning opportunities, and general knowledge. She enjoys sharing her insights through blogs and articles that inform and inspire her readers. When she’s not writing, you’ll likely find her hopping between bookstores and bakeries, always in search of her next favorite read or treat.

Editor's Recommendations

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.