Quick Summary

Table of Contents

The Durand Line is a 2,670-kilometer-long boundary that separates Afghanistan and Pakistan, cutting through rugged mountains, tribal territories, and centuries of shared cultural history. Drawn in 1893 by British diplomat Sir Mortimer Durand, it was initially meant to define the limits of British India’s influence and the Afghan kingdom’s authority. However, a colonial-era strategic demarcation soon became one of South Asia’s most disputed borders.

To this day, the Durand Line remains a source of deep political tension and national identity conflict, particularly because Afghanistan has never officially recognized it as a legitimate international boundary. The border divides ethnic Pashtun communities and disrupts traditional tribal networks, fueling disputes over sovereignty and territorial control. Modern geopolitics continues to shape the dynamics of Pakistan–Afghanistan relations, cross-border militancy, and regional security strategies. Therefore, understanding the Durand Line is essential to grasping the complex interplay of history, colonial legacy, and contemporary power politics that define South Asia’s frontier region.

In the late 19th century, Central Asia became the focus of intense rivalry between the British and Russian empires, a contest known as “The Great Game.” Russia’s southward expansion toward Afghanistan alarmed the British, who feared it could threaten the security of British India or enable Russia to install a pro-Russian regime in Kabul. To protect their prized colony, the British aimed to establish a clearly demarcated frontier for defensive and administrative purposes. Afghanistan, between Russian-controlled regions and British India, became central to this strategic balance.

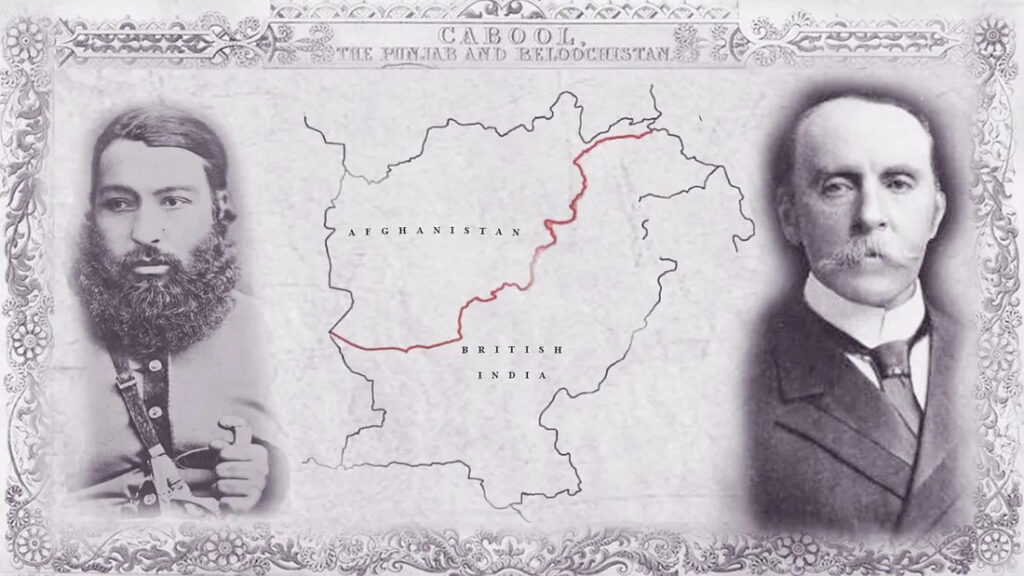

In 1893, the British appointed Sir Mortimer Durand, Foreign Secretary of British India, to negotiate with the Afghan ruler Amir Abdur Rahman Khan. Durand’s mission was to define the northwestern boundary of British India, clarify spheres of influence, and prevent future disputes. The British sought to formalize control over tribal areas west of the Indus River while keeping Afghanistan a neutral buffer state.

The resulting Durand Agreement (1893) delineated the border, but its implementation proved controversial. It split Pashtun communities, disrupted traditional governance, and created lasting social and political grievances. Durand’s role thus became a pivotal moment in colonial frontier policy, shaping a boundary that continues to influence Afghan–Pakistani relations and South Asian geopolitics more than a century later.

The 1893 Durand Line Agreement was a landmark treaty formally establishing the British India and Afghanistan boundary. It was signed during the colonial era and laid the foundation for one of South Asia’s most contentious borders.

The agreement was signed on 12 November 1893 between Sir Mortimer Durand, Foreign Secretary of British India, and Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, ruler of Afghanistan, at Kabul. It aimed to define the political boundary between British-controlled territories and Afghanistan, framed as a mutual understanding of “spheres of influence,” but primarily driven by British strategic interests. Knowing of the power imbalance, Amir Abdur Rahman Khan agreed to secure recognition of his sovereignty and continued British subsidies. The treaty redrew the region’s geopolitical map and established a disputed border.

The Durand Line stretched approximately 2,640 kilometers (1,640 miles) from the Chitral region in the north to Balochistan in the south. It cut through Pashtun and Baloch tribal areas, dividing families and communities, and affected six Afghan provinces: Kunar, Nangarhar, Khost, Paktia, Paktika, and Kandahar. The British gained control over strategic areas such as Waziristan, Kurram, and the Khyber Pass. Although the treaty forbade interference beyond the frontier, its enforcement was inconsistent due to the rugged terrain and complex tribal dynamics, making control difficult.

For British India, the Durand Line was a cornerstone of its frontier security policy. It offered a more transparent and more defensible boundary, reducing the risk of Russian infiltration through Afghanistan. By incorporating the tribal belt into the British sphere, the Raj gained control over vital passes like the Khyber and Bolan, enabling surveillance and rapid troop deployment in case of external threats.

Moreover, the line helped consolidate the concept of Afghanistan as a buffer state, a neutral zone insulating British India from Russian expansionism. Strategically, it allowed the British to manage tribal affairs indirectly, maintaining influence without full-scale annexation. The Durand Line embodied the imperial balance of power during the late 19th century, ensuring British dominance in South Asia’s geopolitically sensitive northwest frontier.

Although established in 1893, the Durand Line continued to shape Afghan–British and later Afghan–Pakistani relations, influencing politics, sovereignty debates, and regional security. Successive rulers and the major political changes of the 20th century carried forward its legacy.

After the death of Amir Abdur Rahman Khan in 1901, his son, Amir Habibullah Khan (1901–1919), initially followed a policy of cautious cooperation with the British. In 1905, both governments reaffirmed the Durand Line, renewing the terms of the 1893 agreement. Later, after the Third Anglo-Afghan War (1919), King Amanullah Khan sought complete Afghan independence. Treaties such as the Treaty of Rawalpindi (1919) and the Anglo-Afghan Treaty (1921) reaffirmed the border. Yet, Afghan rulers continued to view it as a symbol of imposed colonial control, sowing seeds for future disputes.

The creation of Pakistan in 1947 brought new tensions, as Afghanistan refused to recognize the Durand Line under the new state, claiming the treaty had expired with British rule and that Pashtun tribes should decide their fate. Afghanistan’s stance included voting against Pakistan’s admission to the United Nations. Over the decades, the Durand Line became a persistent source of friction, affecting cross-border tribal relations, refugee movements, and militant activity. The issue remains unresolved, continuing to influence regional politics and security in South Asia.

The Durand Line stretches across some of South Asia’s most rugged and strategically significant terrain, forming the international boundary between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Its path has shaped tribal, cultural, and security dynamics for over a century.

The Durand Line extends approximately 2,640 kilometers (1,640 miles), starting from the Wakhan Corridor in Afghanistan’s northeast and descending southwest through the Hindu Kush and Safed Koh ranges. It passes across numerous tribal regions before reaching the Balochistan plateau in the south, terminating near the Iranian border where Pakistan’s Balochistan meets Afghanistan’s Nimroz province. The line divides two sovereign nations while intersecting communities with centuries-old ethnic and cultural ties.

On the Pakistani side, the boundary runs through Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, cutting across tribal areas like Waziristan, Kurram, Mohmand, Bajaur, and the Khyber Agency. On the Afghan side, it passes through Nangarhar, Kunar, Paktia, Paktika, Khost, Kandahar, and Nimroz. These regions are home to the Pashtun tribes, whose social, linguistic, and familial connections predate the border. Historically, the Durand Line functioned more as a frontier zone than a fixed boundary, with fluid movement of people and goods.

The frontier includes key mountain passes like the Khyber Pass and Bolan Pass, which are vital for trade and military movements. The rugged terrain of mountains, plateaus, and semi-deserts complicates border management and enforcement. This geography has contributed to the porosity of the line, allowing tribes, traders, and militants to move freely, sustaining cultural continuity while posing persistent security challenges for both nations.

Since its creation in 1893, the Durand Line has remained one of South Asia’s most contentious borders. Disputes over its legitimacy continue to shape Afghanistan–Pakistan relations, affecting politics, security, and regional stability.

Afghanistan’s rejection of the Durand Line stems from historical, legal, and ethnic grievances. Afghan leaders claim the 1893 agreement was signed under British coercion, making it illegitimate by modern standards. They argue the treaty was personal to Amir Abdur Rahman Khan and expired either with his death or the end of British rule in 1947.

Beyond legal concerns, the border divides the Pashtun population, splitting tribes and families across Afghanistan and Pakistan. Afghan nationalists view this as a threat to national unity and sovereignty. As a result, successive Afghan governments have refused to recognize the Durand Line as a permanent international boundary, regarding it as a colonial imposition made without the consent of the affected people.

Pakistan maintains that the Durand Line is a legitimate international border, inherited from British India upon independence in 1947. Its position rests on the legal principle of Uti possidetis juris, which holds that newly formed states retain the borders of their predecessor colonial entities. Pakistan argues that Afghanistan reaffirmed the border multiple times in 1905, 1919, and 1921 and that no formal treaty annulled these agreements.

Moreover, the line has been administered as a de facto boundary for over a century, reinforcing its legal and practical validity. Islamabad views Afghanistan’s objections as politically motivated and asserts that the border’s recognition is essential for regional stability, border management, and counterterrorism efforts.

The international community, including the United Nations, essentially recognizes the Durand Line as the de facto international border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Although the UN has not formally declared the matter, global diplomatic practice treats Pakistan’s control of the Durand Line as legitimate.

Major powers such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and China acknowledge Pakistan’s sovereignty over its side of the frontier. Most international maps and treaties reflect this alignment. However, due to Afghanistan’s internal instability and political sensitivities, few countries openly press Kabul to recognize the border officially. Thus, while de facto recognition prevails, the issue remains a political and emotional flashpoint in Afghan–Pakistani relations, complicating regional peace and cooperation.

The Durand Line has profoundly shaped the Afghanistan-Pakistan frontier, influencing tribal identities, cross-border relations, and regional security for over a century. Its legacy continues to affect South Asia’s politics, culture, and security dynamics.

The Durand Line split the Pashtun population, dividing tribes and communities that historically shared culture, language, and family ties. Clans were forced to live under separate national administrations while maintaining cross-border social and economic interactions. This disrupted traditional governance, trade, and seasonal migration, creating long-standing grievances. Afghan Pashtuns view the border as a colonial imposition, while Pakistani Pashtuns balance loyalty to the state with tribal affiliations. The separation continues to influence local identity, politics, and cross-border relations, underscoring the frontier’s enduring social and cultural impact.

The porous frontier has enabled smuggling, insurgency, and militant infiltration. Groups like the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) exploit rugged terrain to move personnel, weapons, and resources. Pakistan undertook fencing and border management from 2017 to 2023, including barbed wire barriers, checkpoints, and surveillance posts to address this. While these measures have limited illegal crossings and militant movement, enforcement remains challenging due to the mountains, deserts, and autonomous tribal areas. The Durand Line remains a flashpoint for cross-border instability.

The Durand Line is central to regional security and geopolitics. Following the US and NATO withdrawal in 2021, it became crucial for Pakistan’s counterterrorism planning, refugee management, and strategic operations. The border also affects regional infrastructure and connectivity projects, including the China-Pakistan-Afghanistan economic corridor. Its stability continues to shape diplomacy, trade, and security partnerships in South and Central Asia.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Total Length | ~2,640 km |

| Drawn In | 1893 |

| Signed Between | Sir Mortimer Durand & Amir Abdur Rahman Khan |

| Countries Divided | Afghanistan and Pakistan |

| Status | Disputed by Afghanistan, accepted by Pakistan |

| Major Passes | Khyber Pass, Bolan Pass |

These concise points provide a quick reference for understanding the Durand Line’s historical, geopolitical, and strategic significance, making it ideal for exams and rapid revision.

The Durand Line is one of South Asia’s most historically significant and politically sensitive borders. Established in 1893 through an agreement between Sir Mortimer Durand and Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, it was intended to serve as a clear frontier between British India and Afghanistan, acting as a buffer against Russian expansion. Over time, however, the line divided ethnic Pashtun communities, altered traditional tribal structures, and became a symbol of colonial imposition.

In the modern era, the Durand Line continues to influence Afghanistan–Pakistan relations, shaping security dynamics, cross-border movement, and regional diplomacy. Disputes over its legitimacy have fueled tensions, while Pakistan’s efforts to manage the frontier through fencing and surveillance underscore its strategic importance. The border also plays a crucial role in emerging infrastructure and connectivity initiatives, such as the China-Pakistan corridor, highlighting its continuing relevance in South Asian geopolitics.

Ultimately, the Durand Line exemplifies how colonial-era decisions leave enduring legacies, affecting societies, politics, and international relations long after independence. Its history reminds us that borders are not just lines on a map but living markers of culture, conflict, and power, with consequences that resonate across generations.

Read More:-

The Durand Line is the international border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, established in 1893 by Sir Mortimer Durand of British India and Afghan ruler Amir Abdur Rahman Khan. Stretching about 2,640 km, it divides the Pashtun tribal areas and remains a contentious boundary, influencing regional politics and security.

India and Afghanistan do not share a direct land border. The two countries are separated by Pakistan, including the regions of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. Historically, their access has relied on trade and strategic routes through Pakistan, making India-Afghanistan relations dependent on cross-border connectivity.

Afghanistan does not recognize the Durand Line because it was imposed under British colonial pressure in 1893. Afghan leaders argue the treaty expired with British rule in 1947, and the border unfairly divides the Pashtun ethnic population, undermining Afghanistan’s sovereignty and national unity.

The Durand Line stretches approximately 2,640 kilometers (1,640 miles) and forms the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. It runs from the Wakhan Corridor in the northeast of Afghanistan to the Balochistan region in the southwest, cutting through rugged mountains, tribal areas, and key strategic passes like the Khyber and Bolan Passes.

The Durand Line Agreement was signed on 12 November 1893 between Sir Mortimer Durand, the Foreign Secretary of British India, and Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, the ruler of Afghanistan. The treaty aimed to define the boundary between British India and Afghanistan, establish spheres of influence, and largely serve British strategic interests.

Authored by, Muskan Gupta

Content Curator

Muskan believes learning should feel like an adventure, not a chore. With years of experience in content creation and strategy, she specializes in educational topics, online earning opportunities, and general knowledge. She enjoys sharing her insights through blogs and articles that inform and inspire her readers. When she’s not writing, you’ll likely find her hopping between bookstores and bakeries, always in search of her next favorite read or treat.

Editor's Recommendations

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.