Table of Contents

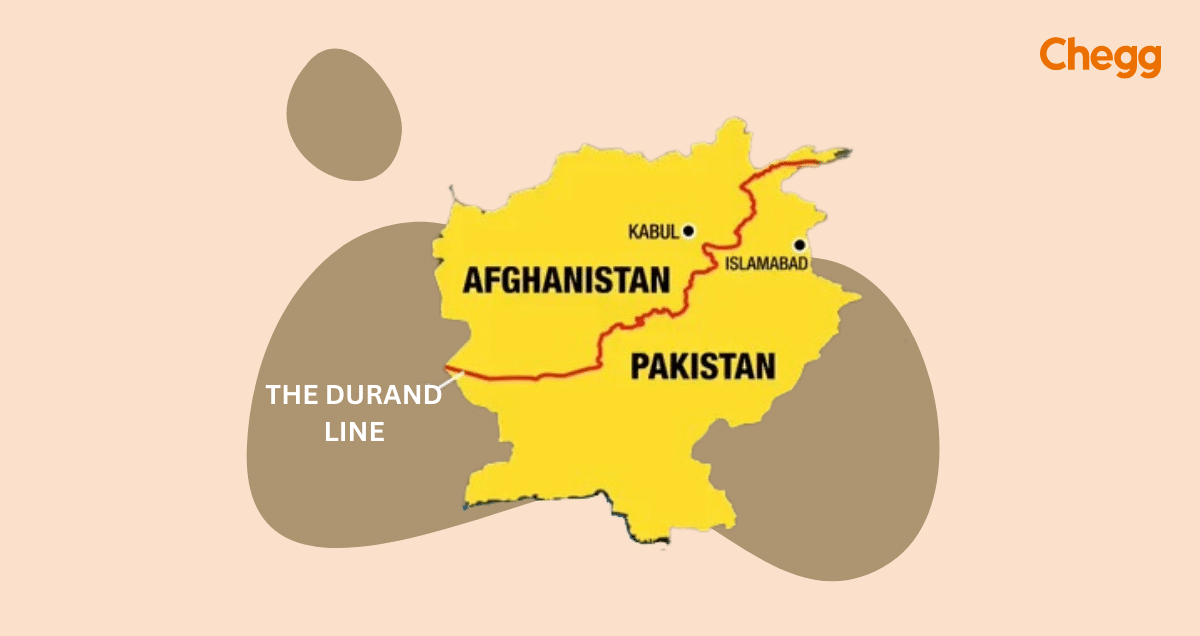

The Durand Line is a significant, but controversial, border separating Afghanistan and Pakistan. It was established in 1893 by Sir Mortimer Durand, a British diplomat, and Abdur Rahman Khan, the Emir of Afghanistan. The border stretches roughly 2,640 kilometers (1,640 miles) from the Iranian border in the west to the Chinese border in the east. This border was created to define the spheres of influence between British India and Afghanistan, aiming to improve diplomatic relations and trade.

Because the line was drawn based on political considerations, not ethnic or tribal boundaries, It divided the Pashtun communities, a major ethnic group residing on both sides of the border.

The Durand Line’s legitimacy has been a point of contention for Afghanistan, particularly regarding its enforcement and impact on Pashtun aspirations for unification.

Despite the controversy, It remains the internationally recognized border between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Origin and History of the Durand Line

The Durand Line originates in the 19th-century power struggles between the British Empire and Afghanistan. In the late 1800s, British India sought to solidify its northwestern frontier. They aimed to create a buffer zone between their territory and the growing power of Russia, which was expanding into Central Asia.

- Negotiation and Agreement: Sir Mortimer Durand, a British diplomat, negotiated with Abdur Rahman Khan, the Emir of Afghanistan, in 1893. Their agreement established the Durand Line as the official border between British India and Afghanistan.

- Purpose: The primary purpose of the Line was to define the spheres of influence of the British and Afghan empires. It aimed to maintain stability in the region and improve diplomatic relations.

- A crucial point to note is that the Durand Line sliced through the tribal lands of the Pashtun people, dividing them between British India (present-day Pakistan) and Afghanistan. This has had lasting consequences, contributing to tensions along the border even today.

So, the Durand Line emerged from a mix of British geopolitical interests and negotiations with the Afghan ruler, but it came at the cost of dividing Pashtun communities.

Impact on Pakistan-Afghan Relations

- Divided Pashtuns: The Durand Line cuts through Pashtun tribal lands, separating families and communities. This fuels Pashtun nationalism and movements for unification, creating instability in both Afghanistan and Pakistan.

- Unresolved Border Dispute: Afghanistan has never formally recognized the Durand Line, arguing it’s an illegitimate imposition. This unresolved dispute creates constant tension and hinders trust-building between the two countries.

- Sanctuary for Militants: The porous border allows militant groups like the Taliban to find safe havens on either side. This impacts regional security and fuels suspicion between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

- Limited Access for Afghanistan: As Pakistan controls the main land route to the Arabian Sea, Afghanistan remains landlocked. This dependence strengthens Pakistan’s strategic position and hinders Afghanistan’s economic development.

- Geopolitical Tug-of-War: The Durand Line becomes a pawn in the larger regional game. External powers can exploit tensions to further their interests, adding another layer of complexity.

Durand Line on India Map

Durand Line spans over 2,650 Kilometers. Its longitudinal extent covers regions of Iran right up to China. More specifically, it covers Balochistan, Gilgit-Baltistan, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa of Pakistan.

The Durand Line between India and Afghanistan is no longer a part of the Indian Map. The partition of Pakistan in 1947 withdrew India from this.

Also Read:-

Bhils: The Largest Tribe in India & Much More About Indian Tribes

Iron Ore Mines in India: Unearthing India’s Iron Wealth

Neighboring Countries of India: Namеs, Capitals, Bordеrs & Morе

Controversies and Disputes

The historical disputes run parallel with the modern-day concerns. Despite marginal differences in form and expression, it sheds light on how little has changed. The Durand Line dispute is the culprit behind two dehumanizing acts against Afghanistan: The third Anglo-Afghan War and the Jalalabad Bombing.

Influence on Regional Politics

Durand Line provoked the Pashtun-Punjabi dispute. It harbored harmful sentiments against divided regions. It also collectively contributed to the flaws in the political system.

Border Incidents and Cross-Border Movements

Some speculate that the Durand Line is a means to illegal trade. The smuggling of substances is also a point of concern. Moreover, the expansion of Frontier Corps threatens the people living there. It directly restricts the free movement of militants and families.

Records of Pakistan pushing its borders into Chaman after 2001 were also noticed. It built into the case that the conflict over the Durand Line could all be a ploy for greater political moves.

Present Status of the Durand Line

The Durand Line’s present status is complex and a point of contention between Afghanistan and Pakistan. In 1999, Afghanistan pointed to the overdue period of the Durand Commission. It implies that the grounds go back to its home nation. However, Pakistan declared this claim void.

The Durand Line is internationally recognized as the western border of Pakistan. Most countries accept it as a legitimate border. However, the Afghan government has never officially accepted it as its border with Pakistan. They argue that it was an agreement made by a colonial power that disregarded tribal affiliations.

The division of Pashtun lands by the Durand Line continues to be a source of tension. Pashtuns on both sides of the border have advocated for greater autonomy or even an independent Pashtun state.

Its porous nature creates challenges for border control. This has been a factor in the movement of militants and instability in the region. The Durand Line has witnessed the movement of up to 60,000 unmonitored people. In 2006, Pakistan raised a fence along the border.

In essence, the Durand Line remains a contested border despite international recognition. It remains to be the epicenter of South Asian politics. Access to the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean is the reward either nation is chasing. International disputes surrounding the border led to UN interference. The panel introduced decorum. However, distress continues between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Frequently Asked Questions ( FAQ’s )

The boundary separating Afghanistan and Pakistan is known as the Durand Line. Its validity as a boundary is the main point of dispute in the current conflict. Afghanistan disagrees with it and claims its right to a portion of the territory on the Pakistani side. Tension between the two nations results from this disagreement, which has persisted for a long time without a solution.

The British governor, Sir Mortimer Durand, drew an agreement with Abdur Rahman Khan. The deed is named after Mortimer Durand, a British Indian official.

The Durand Line is important because it defines the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. The British developed it in the 19th century, and people in these nations remain affected today. Some communities, like the Pashtuns and Balochs, are divided due to disagreements and conflicts caused by the border.

Pakistan is the country that fenced the Durand Line border. They built a barrier to mark the boundary between Pakistan and Afghanistan. They constructed this fence to manage the movement of people and goods across the border and to address security concerns.

Got a question on this topic?