Quick Summary

The Juvenile Justice Act provides a legal framework for the care, protection, and rehabilitation of minors in India.

It differentiates between a child in conflict with law and a child in need of care and protection.

The JJ Act 2015 allows juveniles aged 16–18 to be tried as adults for heinous crimes.

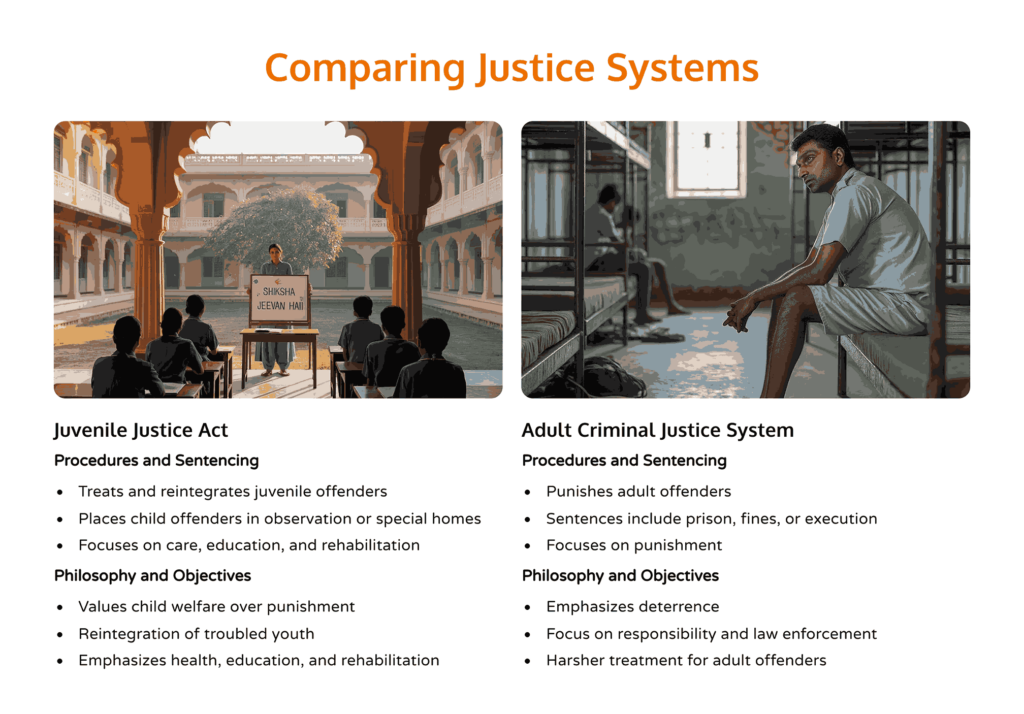

It emphasizes child rights, institutional accountability, and rehabilitation over punishment, diverging from the adult criminal justice system.

Table of Contents

The Juvenile Justice Act was introduced as a foundational legal framework intended to address the unique needs of minors in India. It has been structured to treat children not as adult offenders but as individuals capable of transformation, deserving of a system grounded in protection and rehabilitation. The purpose of introducing the juvenile justice act was to create an environment that nurtures reform rather than imposes punishment.

This legislation explicitly distinguished between juvenile offenders and adult criminals. By recognizing developmental and psychological immaturity, the juvenile justice system has been adapted to uphold child rights in alignment with international treaties, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. These guiding frameworks have strongly influenced the adoption of a more empathetic and individualized approach.

It has been observed, for example, that when a 16-year-old is apprehended for theft committed under the burden of socioeconomic stress, they are processed not through the adult criminal justice system but through mechanisms such as observation homes. This divergence in treatment exemplifies how juvenile justice principles differ significantly from adult criminal prosecution.

A Juvenile in Conflict with the Law refers to a child or adolescent who has committed an offense or is accused of violating the law. The term specifically applies to individuals under 18 years (as per most national and international standards), who are treated differently from adults within the criminal justice system. The goal in handling juveniles in conflict with the law is not just punishment but rehabilitation, reformation, and reintegration into society.

Juvenile Justice Act (Care and Protection of Children), 2015 was passed on 7 May 2015 by the Lok Sabha amid intense protests by several Members of Parliament. It replaced the Indian juvenile delinquency law and the Juvenile Justice Act (Care and Protection of Children) of 2000. It allows juveniles in conflict with the Law in the age group of 16–18, involved in Heinous Offences, to be tried as adults.

The Juvenile Justice Act has been further amended by the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Amendment Act, 2021, which came into force on 1 September 2022.

India did not establish a juvenile offender age of majority until 1960. The definition of “child” varied from state to state and was never consistent. The Bombay Children Act of 1948 defines children as boys under 16 and girls under 18. In the 18th century, the UK and the US pioneered juvenile offender care. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child from 1989 puts kids’ needs first.

After independence, the Indian Constitution acknowledged the need for legislation to safeguard children and juvenile offenders. The Children’s Act of 1960 funded programs that helped disadvantaged kids and those who had committed juvenile offenses. The Act also established residential observation facilities and unique educational programs. The 1996 Juvenile Justice Act 1986 revision incorporated the United Nations Minimum Rules for Juvenile Justice.

Instead, the 2000 Juvenile Justice Act followed the UN Conventions. After the Nirbhaya Delhi gang rape, the government tightened juvenile justice with the Juvenile Justice Act (Care and Protection of Children), 2015. Even severely delinquent youth have access to current opportunities and services under the law. Section 15 of the Juvenile Justice Act allows juveniles to be tried as adults for serious crimes.

The Juvenile Justice Act of 1986 was a significant piece of legislation in India aimed at addressing the needs of children in two main categories:

The Juvenile Justice Act 2000 is the main child protection law. This law creates a new system for addressing and preventing adolescent and young adult issues. It describes how the juvenile justice system will safeguard and heal children. This juvenile law resembles the 1989 UNCRC. India replaced the Juvenile Justice Act 1986 with this law in 1992 after ratifying the UNCRC.

The Juvenile Justice Act aimed to standardize and streamline legal protections and care for youth in legal trouble. It emphasized safe, caring environments to meet children’s changing needs. A child-centered approach to case adjudication and resolution protected the children’s best interests and empowered them to be rehabilitated in this law’s facilities. By raising the age of majority from 14 to 18, the Juvenile Justice Act greatly improved the situation. Unfair practices like child marriages and human trafficking prompted these reforms.

In 2000, lawmakers in the United Kingdom passed the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act to aid minors who had gotten into legal trouble. However, the Delhi gang rape and murder case in 2012 brought attention to systemic shortcomings. The Juvenile Justice Reform Act of 2000 mandates a three-year sentence for this minor defendant. After widespread public outcry, people called for more stringent measures to deal with violent youth offenders. As a result of public outcry, lawmakers revised the law to address what they saw as a miscarriage of justice.

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Amendment Bill, 2015, addressed public concerns. The primary goals of the revision were to:

Under the new juvenile law, authorities can try teens who commit serious crimes between 16 and 18 as adults.

The Juvenile Justice Board would consider mental and physical maturity, the ability to understand consequences, and crime involvement to decide whether to try the juvenile as an adult.

Despite strict rules, the goal has always been to reform and rehabilitate youth offenders.

The amendment also addressed these problems. On December 22, the Parliament approved the amendment, which went into effect on January 15 of the following year.

The General Principles of Care and Protection of Children are fundamental guidelines for ensuring the well-being and rights of children, particularly those in difficult circumstances such as children in conflict with the law, children in need of care and protection, or those affected by abuse or neglect. These principles are enshrined in various child protection laws, including the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, in India. They are based on internationally recognized frameworks like the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). If you are looking for your own copy of Juvenile Justice Act, you may download be from below given link.

Key principles include:

1. Best Interest of the Child

2. Non-Discrimination

3. Right to Protection from Harm

4. Participation

5. Rehabilitation and Reintegration

6. Right to Education

7. Right to Health and Welfare

8. Family Preservation

9. Accountability

10. Social Justice

11. Special Protection for Vulnerable Groups

These principles ensure that children’s rights are upheld in all situations, whether they are living with their families, in institutions, or facing conflict with the law. They guide child protection agencies, governments, and communities in creating environments that nurture and support children’s development into healthy, productive adults.

| Enactment Date: | December 31, 2015 |

| Short Title: | The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 |

| Long Title: | This bill makes it easier for children suspected of breaking the law or needing care and protection to get it. The bill requires basic care, security, development, treatment, social reintegration, and a child-friendly approach to cases decided in children’s best interests and their rehabilitation through processes, institutions, and bodies. |

| Ministry: | Ministry of Women and Child Development |

| Enforcement Date: | January 15, 2016 |

Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 (JJ Act 2015) protects children and lawbreakers. The Act shows India’s dedication to youth development.

The following is a list of the main clauses of the JJA, 2015:

The Juvenile Justice Act of 2015 establishes children’s rights and emphasizes the state’s duty to protect, advance, and ensure these rights. The Act:

The JJA, 2015 emphasizes care, protection, and accountability, especially for older juveniles who commit serious crimes. Juvenile Justice Act Section 15 penalizes offenders.

The 2015 Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act created a statewide juvenile justice system in India. This system protects children’s rights and holds adults accountable. It shows India’s commitment to fairness, compassion, and youth rights.

Juvenile Justice Boards have been instituted under the Juvenile Justice Act to hear and decide cases involving children in conflict with the law. Each board has a metropolitan or judicial magistrate and two social workers, at least one of whom must be a woman. The proceedings are intended to be child-friendly and non-adversarial, ensuring that minors are not intimidated or unduly stressed by the judicial environment.

The JJB is empowered to assess whether a child alleged to have committed a heinous crime between the ages of 16 and 18 should be tried as an adult. This assessment includes an inquiry into the child’s mental and physical capacity to commit such an offense and understand its consequences. The final determination significantly influences whether the juvenile remains within the protective system or is transferred to be tried as an adult.

For example, in a case involving a 17-year-old accused of homicide, the JJB would undertake a thorough evaluation. The board may call upon psychologists, counselors, and other experts before deciding on the trial mode. This critical role underscores the board’s responsibility to balance accountability with the child’s right to rehabilitation.

Child Welfare Committees serve as the apex bodies for the care, protection, and rehabilitation of needy children. Each district must have at least one CWC, and its members are expected to have experience in child development, health, or welfare. The CWCs function with quasi-judicial powers and make legally binding decisions regarding children’s placement, care, and protection.

When children are found abandoned, orphaned, or rescued from abusive environments, they are produced before the CWC. The committee then evaluates the child’s condition and circumstances and decides on measures such as restoration to the family, admission to a children’s home, or placing the child in foster care. Their decisions are guided by the principle of the child’s best interest.

For instance, if a child is rescued from illegal child labor, the CWC may order temporary shelter placement and initiate steps to reunite the child with their family, only if it is deemed safe and supportive. If not, alternative care options such as institutional or foster care are considered.

Child care institutions, such as observation homes, special homes, shelter homes, and fit facilities, are critical components of the juvenile justice system. Observation homes temporarily take custody of children during the pendency of inquiry, while special homes serve those requiring longer-term rehabilitation after adjudication by the JJB.

These institutions provide more than just housing; they focus on vocational training, basic education, life skills development, and psychological counseling. Staff are trained to maintain a rehabilitative environment conducive to reform rather than punishment. Medical care, nutritious meals, and legal aid are also mandated as part of the services.

For example, a child involved in repeated petty thefts may be placed in a special home, where structured behavioral therapy, skill-building workshops, and a nurturing routine help address the root causes of deviant behavior. This comprehensive institutional support seeks to reduce recidivism and promote reintegration into society.

The Act also provides for placing children in conflict with the law or needing care and protection in fit facilities or with fit persons. These may include registered NGOs, families, or individuals assessed and certified by CWCs as capable of caring for children. The aim is to provide children with a non-institutional, family-like environment conducive to healing and personal growth.

Fit facilities often collaborate with governmental authorities and offer professional services like counseling, educational support, and health care. Foster care is increasingly being promoted as a more humane and individualized alternative to institutional care, particularly for young or traumatized children.

An example includes a certified couple providing foster care to a three-year-old abandoned child. The foster environment enables the child to grow in a familial setting while the state monitors and supports their welfare until permanent arrangements are made.

These institutions collectively embody the spirit of the Juvenile Justice Act—providing not just legal remedy, but comprehensive rehabilitation and protection aimed at building futures for vulnerable and at-risk children.

Under the Juvenile Justice Act, various institutions have been set up to ensure the Act’s objectives are achieved. Juvenile Justice Boards have been formed to adjudicate cases involving children in conflict with the law. These boards consist of a judicial magistrate and two social workers; all proceedings are child-sensitive.

Child Welfare Committees operate as the authority for children needing care and protection. Their responsibilities include making decisions regarding foster care, adoption, and restoration to families, ensuring that children are placed in the most suitable rehabilitative settings.

In practical terms, if a minor is found abandoned in a railway station, the child would be brought before the Child Welfare Committee. Based on the child’s needs and circumstances, placement in a shelter home or initiation of adoption procedures would be ordered.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Name of the Act | The Juvenile Justice Act (Care and Protection of Children) |

| Date of Passing | 12 August 2014 |

| Date of Enactment | 15 January 2016 |

| Nodal Ministry | Ministry of Women and Child Development |

| Objective | To strengthen and amend the law relating to children in conflict with the law and those needing care and protection |

| Minister of Women and Child Development | Smt. Annpurna Devi (As of May 2025) |

The Juvenile Justice Act has been lauded as a progressive statute that treats juveniles as individuals capable of change. By emphasizing reformative justice over punitive action, the Act has aimed to protect children from the lifelong consequences of early mistakes.

Nonetheless, the success of the juvenile justice system hinges on its implementation. Adequate funding, trained staff, and ongoing legal reforms are essential to realize the Act’s goals. Equally critical is public awareness and social support for child rights.

The juvenile justice system is anticipated to evolve in the coming years to address emerging challenges. With robust legal, institutional, and community frameworks, children who falter will be given the tools and opportunities to rebuild their lives.

Read More:-

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act was originally enacted in 2000. It was later amended and replaced by the Juvenile Justice Act 2015, to strengthen child protection and justice provisions.

Any person under eighteen is considered a minor or a juvenile, as per Indian law. Children below the age of 7 cannot be convicted of any crimes, as they lack the decision-making abilities possessed by adults.

The JJ Act 2000 primarily focused on juvenile rehabilitation and child protection, with limited provisions for serious crimes. The JJ Act 2015 introduced stricter measures, allowing juveniles aged 16–18 to be tried as adults for heinous offenses while strengthening child welfare and rehabilitation frameworks.

When minors get into legal trouble, the Juvenile Justice Board steps in to help them out. A judge or magistrate from the mеtropolitan arеa, along with two social workers, make up this group.

The Child Welfare Committee was set up to handle issues involving vulnerable children. When it comes to a child’s wеll-bеing, the court has the final say on matters like adoption.

The Juvenile Justice Act 1986 laid the foundation for child protection and juvenile rehabilitation in India. The Juvenile Justice Act 2015 modernized these provisions, introducing stricter measures for heinous crimes and emphasizing both welfare and accountability.

POCSO stands for Protection of Children from Sexual Offences, as provided under the POCSO Act, 2012.

Authored by, Muskan Gupta

Content Curator

Muskan believes learning should feel like an adventure, not a chore. With years of experience in content creation and strategy, she specializes in educational topics, online earning opportunities, and general knowledge. She enjoys sharing her insights through blogs and articles that inform and inspire her readers. When she’s not writing, you’ll likely find her hopping between bookstores and bakeries, always in search of her next favorite read or treat.

Editor's Recommendations

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.